| This article is part of a series on the |

| Culture of the United States of America |

|---|

| Society |

|

| Arts and literature |

|

| Other |

|

| Symbols |

|

|

United States portal |

Religion in the United States is characterized by a diversity of religious beliefs and practices. Various religious faiths have flourished within the United States. A majority of Americans report that religion plays a very important role in their lives, a proportion unique among developed countries.[2]Template:Update inline

Historically, the United States has always been marked by religious pluralism and diversity, beginning with various native beliefs of the pre-colonial time. In colonial times, Anglicans, Catholics and mainline Protestants, as well as Jews, arrived from Europe. Eastern Orthodoxy has been present since the Russian colonization of Alaska. Various dissenting Protestants, who left the Church of England, greatly diversified the religious landscape. The Great Awakenings gave birth to multiple evangelical Protestant denominations; membership in Methodist and Baptist churches increased drastically in the Second Great Awakening. In the 18th century, deism found support among American upper classes and thinkers. The Episcopal Church, splitting from the Church of England, came into being in the American Revolution. New Protestant branches like Adventism emerged; Restorationists and other Christians like the Jehovah's Witnesses, the Latter Day Saint movement, Churches of Christ and Church of Christ, Scientist, as well as Unitarian and Universalist communities all spread in the 19th century. Pentecostalism emerged in the early 20th century as a result of the Azusa Street Revival. Scientology emerged in the 1950s. Unitarian Universalism resulted from the merge of Unitarian and Universalist churches in the 20th century. Since the 1990s, the religious share of Christians has decreased due to secularization, while Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, and other religions have spread. Protestantism, historically dominant, ceased to be the religious category of the majority in the early 2010s.

Christianity is the largest religion in the United States with the various Protestant Churches having the most adherents. In 2016, Christians represent 73.7% of the total population, 48.9% identifying as Protestants, 23.0% as Catholics, and 1.8% as Mormons, and are followed by people having no religion with 18.2% of the total population.[1] Judaism is the second-largest religion in the U.S., practised by 2.1% of the population, followed by Islam with 0.8%. Mississippi is the most religious state in the country, with 63% of its adult population described as very religious, saying that religion is important to them and attending religious services almost every week, while New Hampshire, with only 20% of its adult population described as very religious, is the least religious state.[3] The most religious region of the United States is American Samoa (99.3% religious).[4]

History[]

Pilgrims Going to Church by George Henry Boughton (1867)

From early colonial days, when some English and German settlers moved in search of religious freedom, America has been profoundly influenced by religion.[5] That influence continues in American culture, social life, and politics.[6] Several of the original Thirteen Colonies were established by settlers who wished to practice their own religion within a community of like-minded people: the Massachusetts Bay Colony was established by English Puritans (Congregationalists), Pennsylvania by British Quakers, Maryland by English Catholics, and Virginia by English Anglicans. Despite these, and as a result of intervening religious strife and preference in England[7] the Plantation Act 1740 would set official policy for new immigrants coming to British America until the American Revolution.

The text of the First Amendment to the country's Constitution states that "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances." It guarantees the free exercise of religion while also preventing the government from establishing a state religion. However, the states were not bound by the provision and as late as the 1830s Massachusetts provided tax money to local Congregational churches.[8] The Supreme Court since the 1940s has interpreted the Fourteenth Amendment as applying the First Amendment to the state and local governments.

President John Adams and a unanimous Senate endorsed the Treaty of Tripoli in 1797 that stated: "the Government of the United States of America is not, in any sense, founded on the Christian religion."[9]

Expert researchers and authors have referred to the United States as a "Protestant nation" or "founded on Protestant principles,"[10][11][12][13] specifically emphasizing its Calvinist heritage.[14][15][16]

The modern official motto of the United States of America, as established in a 1956 law signed by President Dwight D. Eisenhower, is "In God We Trust".[17][18][19] The phrase first appeared on U.S. coins in 1864.[18]

According to a 2002 survey by the Pew Research Center, nearly 6 in 10 Americans said that religion plays an important role in their lives, compared to 33% in Great Britain, 27% in Italy, 21% in Germany, 12% in Japan, and 11% in France. The survey report stated that the results showed America having a greater similarity to developing nations (where higher percentages say that religion plays an important role) than to other wealthy nations, where religion plays a minor role.[2]

In 1963, 90% of U.S. adults claimed to be Christians while only 2% professed no religious identity.[20] In 2016, 73.7% identified as Christians while 18.2% claimed no religious affiliation.[21]

Freedom of religion[]

The Maryland Toleration Act secured religious liberty in the English colony of Maryland. Similar laws were passed in the Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, Connecticut and Pennsylvania. These laws stood in direct contrast with the Puritan theocratic rule in the Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay colonies.[22]

The United States federal government was the first national government to have no official state-endorsed religion.[23] However, some states had established religions in some form until the 1830s.

Modeling the provisions concerning religion within the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, the framers of the Constitution rejected any religious test for office, and the First Amendment specifically denied the federal government any power to enact any law respecting either an establishment of religion or prohibiting its free exercise, thus protecting any religious organization, institution, or denomination from government interference. The decision was mainly influenced by European Rationalist and Protestant ideals, but was also a consequence of the pragmatic concerns of minority religious groups and small states that did not want to be under the power or influence of a national religion that did not represent them.[24]

Abrahamic religions[]

Christianity[]

The most popular religion in the U.S. is Christianity, comprising the majority of the population (73.7% of adults in 2016).[1] According to the Association of Statisticians of American Religious Bodies newsletter published March 2017, based on data from 2010, Christians were the largest religious population in all 3,143 counties in the country.[25] Roughly 48.9% of Americans are Protestants, 23.0% are Catholics, 1.8% are Mormons (the name commonly used to refer to members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints).[1] Christianity was introduced during the period of European colonization.

Washington National Cathedral, the Episcopal cathedral in Washington, D.C.

According to a 2012 review by the National Council of Churches, the five largest denominations are:[26]

- The Catholic Church, 68,202,492 members

- The Southern Baptist Convention, 16,136,044 members

- The United Methodist Church, 7,679,850 members

- The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 6,157,238 members

- The Church of God in Christ, 5,499,875 members

The Southern Baptist Convention, with over 16 million adherents, is the largest of more than 200[27] distinctly named Protestant denominations.[28] In 2007, members of evangelical churches comprised 26% of the American population, while another 18% belonged to mainline Protestant churches, and 7% belonged to historically black churches.[29]

A 2015 study estimates some 450,000 Christian believers from a Muslim background in the country, most of them belonging to some form of Protestantism.[30] In 2010 there were approximately 180,000 Arab Americans and about 130,000 Iranian Americans who converted from Islam to Christianity. Dudley Woodbury, a Fulbright scholar of Islam, estimates that 20,000 Muslims convert to Christianity annually in the United States.[31]

Mainline Protestant denominations[]

A Congregational church in Cheshire, Connecticut

Historians agree that members of mainline Protestant denominations have played leadership roles in many aspects of American life, including politics, business, science, the arts, and education. They founded most of the country's leading institutes of higher education.[32] According to Harriet Zuckerman, 72% of American Nobel Prize Laureates between 1901 and 1972, have identified from Protestant background.[33]

Episcopalians[34] and Presbyterians[35] tend to be considerably wealthier and better educated than most other religious groups, and numbers of the most wealthy and affluent American families as the Vanderbilts[34] and Astors,[34] Rockefeller,[36] Du Pont, Roosevelt, Forbes, Whitneys,[34] Morgans[34] and Harrimans are Mainline Protestant families,[34] though those affiliated with Judaism are the wealthiest religious group in the United States[37][38] and those affiliated with Catholicism, owing to sheer size, have the largest number of adherents of all groups in the top income bracket.[39]

Some of the first colleges and universities in America, including Harvard,[40] Yale,[41] Princeton,[42] Columbia,[43] Dartmouth,[44] Williams, Bowdoin, Middlebury,[45] and Amherst, all were founded by mainline Protestant denominations. By the 1920s most had weakened or dropped their formal connection with a denomination. James Hunter argues that:

- The private schools and colleges established by the mainline Protestant denominations, as a rule, still want to be known as places that foster values, but few will go so far as to identify those values as Christian.... Overall, the distinctiveness of mainline Protestant identity has largely dissolved since the 1960s.[46]

Christian settlers[]

Beginning around 1600 European settlers introduced Anglican and Puritans religion, as well as Baptist, Presbyterian, Lutheran, Quaker, and Moravian denominations.[47]

The Salt Lake Temple in Salt Lake City, Utah

Beginning in the 16th century, the Spanish (and later the French and English) introduced Catholicism. From the 19th century to the present, Catholics moved to the US in large numbers due to immigration of Italians, Hispanics, Portuguese, French, Polish, Irish, Highland Scots, Dutch, Flemish, Hungarians, Germans, Lebanese (Maronite), and other ethnic groups.

During the 19th century, two main branches of Eastern Christianity also arrived to America. Eastern Orthodoxy was brought to America by Greek, Russian, Ukrainian, Serbian, and other immigrant groups, mainly from Eastern Europe. In the same time, several immigrant groups from the Middle East, mainly Armenians, Copts and Syriacs, brought Oriental Orthodoxy to America.[48][49]

The Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington, D.C., is the largest Catholic church in the US.

Several Christian groups were founded in America during the Great Awakenings. Interdenominational evangelicalism and Pentecostalism emerged; new Protestant denominations such as Adventism; non-denominational movements such as the Restoration Movement (which over time separated into the Churches of Christ, the Christian churches and churches of Christ, and the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ)); Jehovah's Witnesses (called "Bible Students" in the latter part of the 19th century); and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormonism).

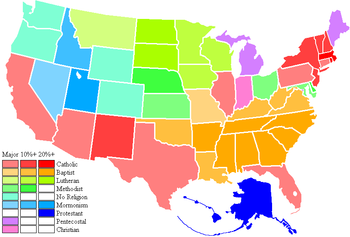

The strength of various sects varies greatly in different regions of the country, with rural parts of the South having many evangelicals but very few Catholics (except Louisiana and the Gulf Coast, and from among the Hispanic community, both of which consist mainly of Catholics), while urbanized areas of the north Atlantic states and Great Lakes, as well as many industrial and mining towns, are heavily Catholic, though still quite mixed, especially due to the heavily Protestant African-American communities. In 1990, nearly 72% of the population of Utah was Mormon, as well as 26% of neighboring Idaho.[50] Lutheranism is most prominent in the Upper Midwest, with North Dakota having the highest percentage of Lutherans (35% according to a 2001 survey).[51]

The largest religion, Christianity, has proportionately diminished since 1990. While the absolute number of Christians rose from 1990 to 2008, the percentage of Christians dropped from 86% to 76%.[52] A nationwide telephone interview of 1,002 adults conducted by The Barna Group found that 70% of American adults believe that God is "the all-powerful, all-knowing creator of the universe who still rules it today", and that 9% of all American adults and 0.5% young adults hold to what the survey defined as a "biblical worldview".[53]

Episcopalian, Presbyterian, Eastern Orthodox and United Church of Christ members[54] have the highest number of graduate and post-graduate degrees per capita of all Christian denominations in the United States,[55][56] as well as the most high-income earners.[57][58] However, owing to the sheer size or demographic head count of Catholics, more individual Catholics have graduate degrees and are in the highest income brackets than have or are individuals of any other religious community.[59]

Judaism[]

After Christianity, Judaism is the next largest religious affiliation in the US, though this identification is not necessarily indicative of religious beliefs or practices.[52] There are between 5.3 and 6.6 million Jews. A significant number of people identify themselves as American Jews on ethnic and cultural grounds, rather than religious ones. For example, 19% of self-identified American Jews do not believe God exists.[60] The 2001 ARIS study projected from its sample that there are about 5.3 million adults in the American Jewish population: 2.83 million adults (1.4% of the U.S. adult population) are estimated to be adherents of Judaism; 1.08 million are estimated to be adherents of no religion; and 1.36 million are estimated to be adherents of a religion other than Judaism.[61] ARIS 2008 estimated about 2.68 million adults (1.2%) in the country identify Judaism as their faith.[52] According to a 2017 study, Judaism is the religion of approximately 2% of the American population.[21]

Touro Synagogue, (built 1759) in Newport, Rhode Island has the oldest still existing synagogue building in the United States.

Jews have been present in what is now the US since the 17th century, and specifically allowed since the British colonial Plantation Act 1740. Although small Western European communities initially developed and grew, large-scale immigration did not take place until the late 19th century, largely as a result of persecutions in parts of Eastern Europe. The Jewish community in the United States is composed predominantly of Ashkenazi Jews whose ancestors emigrated from Central and Eastern Europe. There are, however, small numbers of older (and some recently arrived) communities of Sephardi Jews with roots tracing back to 15th century Iberia (Spain, Portugal, and North Africa). There are also Mizrahi Jews (from the Middle East, Caucasia and Central Asia), as well as much smaller numbers of Ethiopian Jews, Indian Jews, Kaifeng Jews and others from various smaller Jewish ethnic divisions. Approximately 25% of the Jewish American population lives in New York City.[62]

According to the Association of Statisticians of American Religious Bodies newsletter published March, 2017, based on data from 2010, Jews were the largest minority religion in 231 counties out of the 3143 counties in the country.[25] According to a 2014 survey conducted by the Pew Forum on Religion and Public life, 1.7% of adults in the U.S. identify Judaism as their religion. Among those surveyed, 44% said they were Reform Jews, 22% said they were Conservative Jews, and 14% said they were Orthodox Jews.[63][64] According to the 1990 National Jewish Population Survey, 38% of Jews were affiliated with the Reform tradition, 35% were Conservative, 6% were Orthodox, 1% were Reconstructionists, 10% linked themselves to some other tradition, and 10% said they are "just Jewish".[65]

Congregation Shearith Israel (founded 1655) in New York is the oldest Jewish congregation in the United States.

The Pew Research Center report on American Judaism released in October 2013 revealed that 22% of Jewish Americans say they have "no religion" and the majority of respondents do not see religion as the primary constituent of Jewish identity. 62% believe Jewish identity is based primarily in ancestry and culture, only 15% in religion. Among Jews who gave Judaism as their religion, 55% based Jewish identity on ancestry and culture, and 66% did not view belief in God as essential to Judaism.[66]

A 2009 study estimated the Jewish population (including both those who define themselves as Jewish by religion and those who define themselves as Jewish in cultural or ethnic terms) to be between 6.0 and 6.4 million.[67] According to a study done in 2000 there were an estimated 6.14 million Jewish people in the country, about 2% of the population.[68]

According to the 2001 National Jewish Population Survey, 4.3 million American Jewish adults have some sort of strong connection to the Jewish community, whether religious or cultural.[69] Jewishness is generally considered an ethnic identity as well as a religious one. Among the 4.3 million American Jews described as "strongly connected" to Judaism, over 80% have some sort of active engagement with Judaism, ranging from attendance at daily prayer services on one end of the spectrum to attending Passover Seders or lighting Hanukkah candles on the other. The survey also discovered that Jews in the Northeast and Midwest are generally more observant than Jews in the South or West. Reflecting a trend also observed among other religious groups, Jews in the Northwestern United States are typically the least observant of tradition.

The Jewish American community has higher household incomes than average, and is one of the best educated religious communities in the United States.[54]

Islam[]

The Islamic Center of Washington in the nation's capital is a leading American Islamic Center.

Islam is the third largest religion in number in the United States, after Christianity and Judaism, representing the 0.8% of the population in 2016.[1] According to the Association of Statisticians of American Religious Bodies newsletter published in March 2017, based on data from 2010, Muslims were the largest minority religion in 392 counties out of the 3143 counties in the country.[25] According to the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding (ISPU) in 2018, there are approximately 3.45 Muslims living in the United States, with on 2.05 million adults, and the rest being children.[70] Across faith groups, ISPU found in 2017 that Muslims were most likely to be born outside of the US (50%), with 36% having undergone naturalization. American Muslims are also America's most diverse religious community with 25% identifying as black or African American, 24% identifying as white, 18% identifying as Asian/Chinese/Japanese, 18% identifying as Arab, and 5% identifying as Hispanic.[71] In addition to diversity, Americans Muslims are most likely to report being low income, and among those who identify as middle class, the majority are Muslim women, not men. Although American Muslim education levels are similar to other religious communities, namely Christians, within the Muslim American population, Muslim women surpass Muslim men in education, with 31% of Muslim women having graduated from a four year university. 90% of Muslim Americans identify as straight.[71]

Islam in America effectively began with the arrival of African slaves. It is estimated that about 10% of African slaves transported to the United States were Muslim.[72] Most, however, became Christians, and the United States did not have a significant Muslim population until the arrival of immigrants from Arab and East Asian Muslim areas.[73] According to some experts,[74] Islam later gained a higher profile through the Nation of Islam, a religious group that appealed to black Americans after the 1940s; its prominent converts included Malcolm X and Muhammad Ali.[75][76] The first Muslim elected to Congress was Keith Ellison in 2006,[77] followed by André Carson in 2008.[78]

Out of all religious groups surveyed by ISPU, Muslims were found to be the most likely to report experiences of religious discrimination (61%). That can also be broken down when looking at gender (with Muslim women more likely than Muslim men to experience racial discrimination), age (with young people more likely to report experiencing racial discrimination than older people), and race, (with Arab Muslims the most likely to report experiencing religious discrimination). Muslims born in the United States are more likely to experience all three forms of discrimination, gender, religious, and racial.[71] Much of that can potentially be attributed to the rise in Islamophobia or anti-Muslim sentiment in the US, particularly after the September 11 attacks on the World Trade Center, and an on-going culture of media bias and political rhetoric linking Islam and violence.

The Islamic Center of America in Dearborn, Michigan, is the largest mosque in the United States.

Research indicates that Muslims in the United States are generally more assimilated and prosperous than their counterparts in Europe.[79][80][81] Like other subcultural and religious communities, the Islamic community has generated its own political organizations and charity organizations.

ISPU also conducted a series of impact reports on Muslim Americans in both Michigan and New York City. Looking at those two areas alone, the engagement of Muslim Americans is striking. 22.3% of Muslims live in New York City, the home of more mosques (285 total) than any other American city. Though just shy of 9% of the NYC population, Muslims make up over 12% of the cities pharmacists, lab technicians, and over 9% of all doctors. They make up 11.3% of all engineers, and are engaged at every level of civic life in the city, from senior advisor to the city government to dictring outreach at the city council level. Nearly 10,000 NYC teachers are Muslim. Looking at NYC, it is evident that Muslim Americans are engaged and active in important sectors of American life. That level of engagement and dynamic interaction with the communities around them is further highlighted through the Michigan case study as well.[70]

Bahá'í Faith[]

Bahá'í House of Worship (built 1953) in Wilmette, Illinois, is the oldest still existing Bahá'í house of worship in the world and the only one in the United States.

The United States has perhaps the second largest Bahá'í community in the world. First mention of the faith in the U.S. was at the inaugural Parliament of World Religions, which was held at the Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893. In 1894, Ibrahim George Kheiralla, a Syrian Bahá'í immigrant, established a community in the U.S. He later left the main group and founded a rival movement.[82] According to the Association of Statisticians of American Religious Bodies newsletter published March, 2017, based on data from 2010, Bahá'ís were the largest minority religion in 80 counties out of the 3143 counties in the country.[25]

Rastafarianism[]

Rastafarians began migrating to the United States in the 1950s, '60s and '70s from the religion's 1930s birthplace, Jamaica.[83][84] Marcus Garvey, who is considered a prophet by many Rastafarians,[85][86] rose to prominence and cultivated many of his ideas in the United States.

Dharmic religions[]

Buddhism[]

Hsi Lai Temple ("Coming West Temple"), a Buddhist monastery in Hacienda Heights, California, near Los Angeles

Buddhism entered the US during the 19th century with the arrival of the first immigrants from East Asia. The first Buddhist temple was established in San Francisco in 1853 by Chinese Americans.

During the late 19th century Buddhist missionaries from Japan travelled to the US. During the same time period, US intellectuals started to take interest in Buddhism.

Tibetan Buddhist temple in Seattle, Washington

The first prominent US citizen to publicly convert to Buddhism was Henry Steel Olcott in 1880 who is still honored in Sri Lanka for these efforts. An event that contributed to the strengthening of Buddhism in the US was the Parliament of the World's Religions in 1893, which was attended by many Buddhist delegates sent from India, China, Japan, Vietnam, Thailand and Sri Lanka.

The early 20th century was characterized by a continuation of tendencies that had their roots in the 19th century. The second half, by contrast, saw the emergence of new approaches, and the move of Buddhism into the mainstream and making itself a mass and social religious phenomenon.[87][88]

According to a 2016 study, Buddhists are approximately 1% of the American population.[21] According to the Association of Statisticians of American Religious Bodies newsletter published March, 2017, based on data from 2010, Buddhists were the largest minority religion in 186 counties out of the 3143 counties in the country.[25]

Hinduism[]

Swaminarayanan Akshardham Temple Complex in New Jersey, USA

Hinduism is the fourth largest faith in the United States, representing approximately 1% of the population in 2016.[21] The first time Hinduism entered the U.S. is not clearly identifiable. However, large groups of Hindus have immigrated from India and other Asian countries since the enactment of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965. During the 1960s and 1970s Hinduism exercised fascination contributing to the development of New Age thought. During the same decades the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (a Vaishnavite Hindu reform organization) was founded in the US.

In 2001, there were an estimated 766,000 Hindus in the US, about 0.2% of the total population.[89][90] According to the Association of Statisticians of American Religious Bodies newsletter published March, 2017, based on data from 2010, Hindus were the largest minority religion in 92 counties out of the 3143 counties in the country.[25]

In 2003, the Hindu American Foundation—a national institution protecting rights of the Hindu community of U.S.—was founded.

American Hindus have one of the highest rates of educational attainment and household income among all religious communities, and tend to have lower divorce rates.[54]

Jainism[]

Jain Center of Greater Phoenix (JCGP)

Adherents of Jainism first arrived in the United States in the 20th century. The most significant time of Jain immigration was in the early 1970s. The United States has since become a center of the Jain Diaspora. The Federation of Jain Associations in North America is an umbrella organization of local American and Canadian Jain congregations to preserve, practice, and promote Jainism and the Jain way of life.[91]

Sikhism[]

Sikh Center of San Francisco Bay Area, a Sikh Gurdwara in El Sobrante, California.

Sikhism is a religion originating from the Indian subcontinent which was introduced into the United States when, around the turn of the 20th century, Sikhs started emigrating to the United States in significant numbers to work on farms in California. They were the first community to come from India to the US in large numbers.[92] The first Sikh Gurdwara in America was built in Stockton, California, in 1912.[93] In 2007, there were estimated to be between 250,000 and 500,000 Sikhs living in the United States, with the largest populations living on the East and West Coasts, with additional populations in Detroit, Chicago, and Austin.[94][95]

The United States also has a number of non-Punjabi converts to Sikhism.[96]

East Asian religions[]

Taoism[]

In 2004 there were an estimated 56,000 Taoists in the US.[97] Taoism was popularized throughout the world through the writings and teachings of Lao Tzu and other Taoists as well as the practice of Qigong, Tai Chi Chuan and other Chinese martial arts.[98]

No religion[]

In 2016, approximately 18.2% of the Americans declared to be not religiously affiliated.[1]

Agnosticism, atheism, and humanism[]

Atheism promoted on an electronic billboard in Times Square.

A 2001 survey directed by Dr. Ariela Keysar for the City University of New York indicated that, amongst the more than 100 categories of response, "no religious identification" had the greatest increase in population in both absolute and percentage terms. This category included atheists, agnostics, humanists, and others with no stated religious preferences. Figures are up from 14.3 million in 1990 to 34.2 million in 2008, representing an increase from 8% of the total population in 1990 to 15% in 2008.[52] A nationwide Pew Research study published in 2008 put the figure of unaffiliated persons at 16.1%,[90] while another Pew study published in 2012 was described as placing the proportion at about 20% overall and roughly 33% for the 18–29-year-old demographic.[99]

In a 2006 nationwide poll, University of Minnesota researchers found that despite an increasing acceptance of religious diversity, atheists were generally distrusted by other Americans, who trusted them less than Muslims, recent immigrants and other minority groups in "sharing their vision of American society". They also associated atheists with undesirable attributes such as amorality, criminal behavior, rampant materialism and cultural elitism.[100][101] However, the same study also reported that "The researchers also found acceptance or rejection of atheists is related not only to personal religiosity, but also to one's exposure to diversity, education and political orientation – with more educated, East and West Coast Americans more accepting of atheists than their Midwestern counterparts."[102] Some surveys have indicated that doubts about the existence of the divine were growing quickly among Americans under 30.[103]

On 24 March 2012, American atheists sponsored the Reason Rally in Washington, D.C., followed by the American Atheist Convention in Bethesda, Maryland. Organizers called the estimated crowd of 8,000–10,000 the largest-ever US gathering of atheists in one place.[104]

Deism[]

In the United States, Enlightenment philosophy (which itself was heavily inspired by deist ideals) played a major role in creating the principle of religious freedom, expressed in Thomas Jefferson's letters and included in the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. American Founding Fathers, or Framers of the Constitution, who were especially noted for being influenced by such philosophy of deism include Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, Cornelius Harnett, Gouverneur Morris, and Hugh Williamson. Their political speeches show distinct deistic influence. Other notable Founding Fathers may have been more directly deist. These include Thomas Paine, James Madison, possibly Alexander Hamilton, and Ethan Allen.[105]

Belief in the existence of a god[]

Various polls have been conducted to determine Americans' actual beliefs regarding a god:

- In 2014 the Pew Research Center's Religious Landscape Study showed 63% of Americans believed in God and were "absolutely certain" in their view, while the figure rose to 89% including those who were agnostic.[106]

- A 2012 WIN-Gallup International poll showed that 5% of Americans considered themselves "convinced" atheists, which was a fivefold increase from the last time the survey was taken in 2005, and 5% said they did not know or else did not respond.[107]

- A 2012 Pew Research Center survey found that doubts about the existence of a god had grown among younger Americans, with 68% telling Pew they never doubt God's existence, a 15-point drop in five years. In 2007, 83% of American millennials said they never doubted God's existence.[103][108]

- A 2011 Gallup poll found 92% of Americans said yes to the basic question "Do you believe in God?", while 7% said no and 1% had no opinion.[109]

- A 2010 Gallup poll found 80% of Americans believe in a god, 12% believe in a universal spirit, 6% don't believe in either, 1% chose "other", and 1% had no opinion. 80% is a decrease from the 1940s, when Gallup first asked this question.

- A late 2009 online Harris poll of 2,303 U.S. adults (18 and older)[110] found that "82% of adult Americans believe in God", the same number as in two earlier polls in 2005 and 2007. Another 9% said they did not believe in God, and 9% said that they were not sure. It further concluded, "Large majorities also believe in miracles (76%), heaven (75%), that Jesus is God or the Son of God (73%), in angels (72%), the survival of the soul after death (71%), and in the resurrection of Jesus (70%). Less than half (45%) of adults believe in Darwin's theory of evolution but this is more than the 40% who believe in creationism..... Many people consider themselves Christians without necessarily believing in some of the key beliefs of Christianity. However, this is not true of born-again Christians. In addition to their religious beliefs, large minorities of adults, including many Christians, have "pagan" or pre-Christian beliefs such as a belief in ghosts, astrology, witches and reincarnation.... Because the sample is based on those who agreed to participate in the Harris Interactive panel, no estimates of theoretical sampling error can be calculated."

- A 2008 survey of 1,000 people concluded that, based on their stated beliefs rather than their religious identification, 69.5% of Americans believe in a personal God, roughly 12.3% of Americans are atheist or agnostic, and another 12.1% are deistic (believing in a higher power/non-personal God, but no personal God).[52]

- Mark Chaves, a Duke University professor of sociology, religion and divinity, found that 92% of Americans believed in God in 2008, but that significantly fewer Americans have great confidence in their religious leaders than a generation ago.[111]

- According to a 2008 ARIS survey, belief in God varies considerably by region. The lowest rate is in the West with 59% reporting a belief in God, and the highest rate is in the South at 86%.[112]

Spiritual but not religious[]

"Spiritual but not religious" (SBNR) is self-identified stance of spirituality that takes issue with organized religion as the sole or most valuable means of furthering spiritual growth. Spirituality places an emphasis upon the wellbeing of the "mind-body-spirit,"[113] so holistic activities such as tai chi, reiki, and yoga are common within the SBNR movement.[114] In contrast to religion, spirituality has often been associated with the interior life of the individual.[115]

One fifth of the US public and a third of adults under the age of 30 are reportedly unaffiliated with any religion, however they identify as being spiritual in some way. Of these religiously unaffiliated Americans, 37% classify themselves as spiritual but not religious.[116]

Others[]

Native American religions[]

Bear Butte, in South Dakota, is a sacred site for over 30 Plains tribes.

Native American religions historically exhibited much diversity, and are often characterized by animism or panentheism.[117] The membership of Native American religions in the 21st century comprises about 9,000 people.[118]

Neopaganism[]

Neopaganism in the United States is represented by widely different movements and organizations. The largest Neopagan religion is Wicca, followed by Neo-Druidism.[119][120] Other neopagan movements include Germanic Neopaganism, Celtic Reconstructionist Paganism, Hellenic Polytheistic Reconstructionism, and Semitic neopaganism.

Druidry[]

According to the American Religious Identification Survey (ARIS), there are approximately 30,000 druids in the United States.[121] Modern Druidism arrived in North America first in the form of fraternal Druidic organizations in the nineteenth century, and orders such as the Ancient Order of Druids in America were founded as distinct American groups as early as 1912. In 1963, the Reformed Druids of North America (RDNA) was founded by students at Carleton College, Northfield, Minnesota. They adopted elements of Neopaganism into their practices, for instance celebrating the festivals of the Wheel of the Year.[122]

Wicca[]

Wicca advanced in North America in the 1960s by Raymond Buckland, an expatriate Briton who visited Gardner's Isle of Man coven to gain initiation.[123] Universal Eclectic Wicca was popularized in 1969 for a diverse membership drawing from both Dianic and British Traditional Wiccan backgrounds.[124]

Nordic Paganism[]

Nordic Paganism is the umbrella term for polytheistic followers of the Proto-Norse period religions involving the Nordic pantheon of gods. This pantheon includes gods such as the Æsir; Odin, Thor, Loki, Sif, Heimdallr, Baldr, and Týr, as well as goddesses that include Vanir; Freyja, Freyr, Njörðr, and Nerthus. The followers of Nordic Paganism include Odinists, Tyrists, Lokians, Asatru, and practitioners of Seiðr, among other varying followers. Nordic Pagans follow the teachings of the Hávamál. This old text, along with the Prose Edda and Poetic Edda, gives the basis for Norse mythology, stories, legends, and beliefs.

Norse mythology is portrayed in popular culture and Nordic symbols and teachings are also used by many white supremacy groups. This use has prompted some prisons to ban the wearing of these symbols, such as Mjölnir, by inmates due to their gang affiliation.

New Thought Movement[]

Church of the Holy City in Washington, D.C. is tied to the New Church.

A group of churches which started in the 1830s in the United States is known under the banner of "New Thought". These churches share a spiritual, metaphysical and mystical predisposition and understanding of the Bible and were strongly influenced by the Transcendentalist movement, particularly the work of Ralph Waldo Emerson. Another antecedent of this movement was Swedenborgianism, founded on the writings of Emanuel Swedenborg in 1787.[125] The New Thought concept was named by Emma Curtis Hopkins ("teacher of teachers") after Hopkins broke off from Mary Baker Eddy's Church of Christ, Scientist. The movement had been previously known as the Mental Sciences or the Christian Sciences. The three major branches are Religious Science, Unity Church and Divine Science.

Unitarian Universalism[]

Sign on a UU church in Rochester, Minnesota. The denomination stems from the original Congregationalism of the Pilgrim Fathers.

Unitarian Universalists (UUs) are among the most liberal of all religious denominations in America.[126] The shared creed includes beliefs in inherent dignity, a common search for truth, respect for beliefs of others, compassion, and social action.[127] They are unified by their shared search for spiritual growth and by the understanding that an individual's theology is a result of that search and not obedience to an authoritarian requirement.[128] UUs have historical ties to anti-war, civil rights, and LGBT rights movements,[129] as well as providing inclusive church services for the broad spectrum of liberal Christians, liberal Jews, secular humanists, LGBT, Jewish-Christian parents and partners, Earth-centered/Wicca, and Buddhist meditation adherents.[130]

Major religious movements founded in the United States[]

Christian[]

Former New York City headquarters of the Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society run by Jehovah's Witnesses

The First Church of Christ, Scientist in Boston, Massachusetts

- Pentecostalism – movement which emphasizes the role of the Holy Spirit, finds its historic roots in the Azusa Street Revival in Los Angeles from 1904 to 1906, sparked by Charles Parham. It is estimated to have over 279 million followers worldwide, many in Africa and South America.[131]

- Adventism – began as an inter-denominational movement. Its most vocal leader was William Miller, who in the 1830s in New York became convinced of an imminent Second Coming of Jesus. The most prominent modern group to emerge from this is the Seventh-day Adventists.

- The Latter Day Saint movement founded in 1830 by Joseph Smith in upstate New York – a product of the Christian revivalist movement of the Second Great Awakening and based in Christian primitivism. Multiple Latter Day Saint denominations can be found throughout the United States. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), the largest denomination, is headquartered in Salt Lake City, Utah, and it has members in many countries. The Community of Christ, the second-largest denomination, is headquartered in Independence, Missouri. Worldwide they claim about 15 million members.

- Jehovah's Witnesses – originated with the religious movement known as Bible Students, which was founded in Pennsylvania in the late 1870s by Charles Taze Russell. In their early years, the Bible Students were loosely connected with Adventism, and the Jehovah's Witnesses still share some similarities with it. They claim about 7.69 million active members worldwide.

- Christian Science – founded by Mary Baker Eddy in the late 19th century. The church claims some 400,000 members worldwide.

- Churches of Christ/Disciples of Christ – a restoration movement with no governing body. The Restoration Movement solidified as a historical phenomenon in 1832 when restorationists from two major movements championed by Barton W. Stone and Alexander Campbell merged. It has an estimated 3 million followers worldwide.

- Metropolitan Community Church – founded by Troy Perry in Los Angeles, 1968.

- Unitarianism Developed out of the Congregational Churches. In 1825 the American Unitarian Association was formed in Boston, MA.

- Universalist Church of America's first regional conference was founded in 1793.

Other[]

Church of Scientology building in Los Angeles, California

- New Thought Movement – two of the early proponents of New Thought beliefs during the mid to late 19th century were Phineas Parkhurst Quimby and the Mother of New Thought, Emma Curtis Hopkins. The three major branches are Religious Science, Unity Church and Divine Science.

- Scientology – founded by L. Ron Hubbard in 1954. Numbers estimated from a few tens of thousands to 15 million (latter is the religion's estimation in 2004).

- Reconstructionist Judaism – founded by Mordecai Kaplan and started in the 1920s.

- Native American Church – founded by Quanah Parker beginning in the 1890s and incorporating in 1918. An estimated 250,000 followers.

- Nation of Islam – a sect of Islam, created and followed predominantly by African-Americans.

- Church of Satan – founded in San Francisco in 1966 by Anton LaVey.

- Eckankar – founded in Las Vegas in 1965 by Paul Twitchell.

- Self-Realization Fellowship - founded in Los Angeles by Paramahansa Yogananda in 1920.

- Unitarian Universalist Association in 1961 from the consolidation of the American Unitarian Association and the Universalist Church of America. Historically Christian denominations, the UUA is no longer Christian and is the largest Unitarian Universalist denomination in the world.

Government positions[]

The First Amendment guarantees both the free practice of religion and the non-establishment of religion by the federal government (later court decisions have extended that prohibition to the states).[132] The U.S. Pledge of Allegiance was modified in 1954 to add the phrase "under God", in order to distinguish itself from the state atheism espoused by the Soviet Union.[133][134][135][136]

Various American presidents have often stated the importance of religion. On February 20, 1955, President Dwight D. Eisenhower stated that "Recognition of the Supreme Being is the first, the most basic, expression of Americanism."[137] President Gerald Ford agreed with and repeated this statement in 1974.[138]

Statistics[]

The U.S. Census does not ask about religion. Various groups have conducted surveys to determine approximate percentages of those affiliated with each religious group.

2016 Gallup, Inc. data[]

Religion in the United States, Gallup, 18+ (2016)[1]

Gallup carries out since 2008 the Gallup Daily tracking survey, an unprecedented survey of 1,000 U.S. adults each day, 350 days per year.[139] It covers political, economic, wellbeing and demographic topics.[140] Data is weighted to match the U.S. population according to gender, age, race, Hispanic ethnicity, education, region, population density, and phone status in order to correct data for unequal selection probability.[139]

| Affiliation | % of U.S. population | |

|---|---|---|

| Christian | Template:Bartable | |

| Protestant/Other Christian | Template:Bartable | |

| Catholic | Template:Bartable | |

| Mormon | Template:Bartable | |

| None/Atheist/Agnostic | Template:Bartable | |

| Non-Christian faiths | Template:Bartable | |

| Jewish | Template:Bartable | |

| Muslim | Template:Bartable | |

| Other non-Christian religion | Template:Bartable | |

| No response given | Template:Bartable | |

| Total | Template:Bartable | |

2016 Public Religion Research Institute data[]

In 2016, a poll by the Public Religion Research Institute estimated that 69% of the Americans are Christians, with 45% professing attendance at a variety of churches that could be considered Protestant, and 20% professing Catholic beliefs. The same study says that other non-Christian religions (including Judaism, Buddhism, Hinduism, and Islam) collectively make up about 7% of the population.[21]

Religion in the United States (2016)[21]

| Affiliation | % of U.S. population | |

|---|---|---|

| Christian | Template:Bartable | |

| Protestant | Template:Bartable | |

| White Evangelical | Template:Bartable | |

| White Mainline Protestant | Template:Bartable | |

| Black Protestant | Template:Bartable | |

| Hispanic Protestant | Template:Bartable | |

| Other non-white Protestant | Template:Bartable | |

| Catholic | Template:Bartable | |

| White Catholic | Template:Bartable | |

| Hispanic Catholic | Template:Bartable | |

| Other non-white Catholic | Template:Bartable | |

| Mormon | Template:Bartable | |

| Jehovah's Witness | Template:Bartable | |

| Orthodox Christian | Template:Bartable | |

| Unaffiliated | Template:Bartable | |

| Non-Christian | Template:Bartable | |

| Jewish | Template:Bartable | |

| Muslim | Template:Bartable | |

| Buddhist | Template:Bartable | |

| Hindu | Template:Bartable | |

| Other non-Christian | Template:Bartable | |

| Don't know/refused answer | Template:Bartable | |

| Total | Template:Bartable | |

2014 Pew Research Center data[]

| Affiliation | % of U.S. population | |

|---|---|---|

| Christian | Template:Bartable | |

| Protestant | Template:Bartable | |

| Evangelical Protestant | Template:Bartable | |

| Mainline Protestant | Template:Bartable | |

| Black church | Template:Bartable | |

| Catholic | Template:Bartable | |

| Mormon | Template:Bartable | |

| Jehovah's Witnesses | Template:Bartable | |

| Eastern Orthodox | Template:Bartable | |

| Other Christian | Template:Bartable | |

| Unaffiliated | Template:Bartable | |

| Nothing in particular | Template:Bartable | |

| Agnostic | Template:Bartable | |

| Atheist | Template:Bartable | |

| Non-Christian | Template:Bartable | |

| Jewish | Template:Bartable | |

| Muslim | Template:Bartable | |

| Buddhist | Template:Bartable | |

| Hindu | Template:Bartable | |

| Other non-Christian | Template:Bartable | |

| Don't know/refused answer | Template:Bartable | |

| Total | Template:Bartable | |

Attendance[]

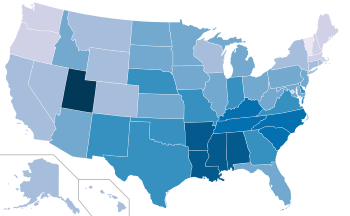

Church, synagogue, or mosque attendance by state (2014)

A 2013 survey reported that 31% of Americans attend religious services at least weekly. It was conducted by the Public Religion Research Institute with a margin of error of 2.5.[141]

In 2006, an online Harris Poll (they stated that the magnitude of errors cannot be estimated due to sampling errors, non-response, etc.; 2,010 U.S. adults were surveyed)[142] found that 26% of those surveyed attended religious services "every week or more often", 9% went "once or twice a month", 21% went "a few times a year", 3% went "once a year", 22% went "less than once a year", and 18% never attend religious services.

In a 2009 Gallup International survey, 41.6%[143] of American citizens said that they attended a church, synagogue, or mosque once a week or almost every week. This percentage is higher than other surveyed Western countries.[144][145] Church attendance varies considerably by state and region. The figures, updated to 2014, ranged from 51% in Utah to 17% in Vermont.

When it comes to mosque attendance specifically, data collected by a 2017 poll by the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding (ISPU) shows that American Muslim women and American Muslim men attend the mosque at similar rates (45% for men and 35% for women).[71] Additionally, when compared to the general public looking at the attendance of religious services, young Muslim Americans attend the mosque at closer rates to older Muslim Americans. Muslim Americans who regularly attend mosques are more likely to work with their neighbors to solve community problems (49 vs. 30 percent), be registered to vote (74 vs. 49 percent), and plan to vote (92 vs. 81 percent). Overall, “there is no correlation between Muslim attitudes toward violence and their frequency of mosque attendance".[71]

| Rank | State | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 51% | |

| 2 | 47% | |

| 3 | 46% | |

| 4 | 46% | |

| 5 | 45% | |

| 6 | 42% | |

| 7 | 42% | |

| 8 | 41% | |

| 9 | 40% | |

| 10 | 39% | |

| 11 | 39% | |

| 12 | 39% | |

| 13 | 36% | |

| 14 | 35% | |

| 15 | 35% | |

| 16 | 35% | |

| 17 | 35% | |

| 18 | 35% | |

| 19 | 34% | |

| 20 | 34% | |

| 21 | 33% | |

| 22 | 33% | |

| 23 | 32% | |

| 24 | 32% | |

| 25 | 32% | |

| 26 | 32% | |

| 27 | 32% | |

| 28 | 32% | |

| 29 | 32% | |

| 30 | 31% | |

| 31 | 31% | |

| 32 | 31% | |

| 33 | 30% | |

| 34 | 29% | |

| 35 | 28% | |

| 36 | 28% | |

| 37 | 28% | |

| 38 | 27% | |

| 39 | 27% | |

| 40 | 27% | |

| 41 | 26% | |

| 42 | 25% | |

| 43 | 25% | |

| 44 | 25% | |

| 45 | 24% | |

| 46 | 24% | |

| 47 | 23% | |

| 48 | 22% | |

| 49 | 20% | |

| 50 | 20% | |

| 51 | 17% |

Territories[]

The following is the percentage of Christians and all religions in the U.S. territories as of 2010:[4][147][148][149][150][151][152][153]

| Territory | Percent Christian |

Percent all religions |

|---|---|---|

| 98.3% | 99.3% | |

| 81.3% | 99% | |

| 94.2% | 98.3% | |

| 89% | 98.1% | |

| 94.8% | 96.3% |

Religion and politics[]

The U.S. guarantees freedom of religion, and some churches in the U.S. take strong stances on political subjects.

In August 2010, 67% of Americans said religion was losing influence, compared with 59% who said this in 2006. Majorities of white evangelical Protestants (79%), white mainline Protestants (67%), black Protestants (56%), Catholics (71%), and the religiously unaffiliated (62%) all agreed that religion was losing influence on American life; 53% of the total public said this was a bad thing, while just 10% see it as a good thing.[154]

Politicians frequently discuss their religion when campaigning, and fundamentalists and black Protestants are highly politically active. However, to keep their status as tax-exempt organizations they must not officially endorse a candidate. Historically Catholics were heavily Democratic before the 1970s, while mainline Protestants comprised the core of the Republican Party. Those patterns have faded away—Catholics, for example, now split about 50–50. However, white evangelicals since 1980 have made up a solidly Republican group that favors conservative candidates. Secular voters are increasingly Democratic.[155]

Only three presidential candidates for major parties have been Catholics, all for the Democratic party:

- Alfred E. Smith in presidential election of 1928 was subjected to anti-Catholic rhetoric, which seriously hurt him in the Baptist areas of the South and Lutheran areas of the Midwest, but he did well in the Catholic urban strongholds of the Northeast.

- John F. Kennedy secured the Democratic presidential nomination in 1960. In the 1960 election, Kennedy faced accusations that as a Catholic president he would do as the Pope would tell him to do, a charge that Kennedy refuted in a famous address to Protestant ministers.

- John Kerry, a Catholic, won the Democratic presidential nomination in 2004. In the 2004 election religion was hardly an issue, and most Catholics voted for his Protestant opponent George W. Bush.[156]

Joe Biden is the first Catholic vice president.[157]

Joe Lieberman was the first major presidential candidate that was Jewish, on the Gore–Lieberman campaign of 2000 (although John Kerry and Barry Goldwater both had Jewish ancestry, they were practicing Christians). Bernie Sanders ran against Hillary Clinton in the Democratic primary of 2016. He was the first major Jewish candidate to compete in the presidential primary process. However, Sanders noted during the campaign that he does not actively practice any religion.[158]

In 2006 Keith Ellison of Minnesota became the first Muslim elected to Congress; when re-enacting his swearing-in for photos, he used the copy of the Qur'an once owned by Thomas Jefferson.[159] André Carson is the second Muslim to serve in Congress.

A Gallup poll released in 2007[160] indicated that 53% of Americans would refuse to vote for an atheist as president, up from 48% in 1987 and 1999. But then the number started to drop again and reached record low 43% in 2012 and 40% in 2015.[161][162]

Mitt Romney, the Republican presidential nominee in 2012, is Mormon and a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. He is the former governor of the state of Massachusetts, and his father George Romney was the governor of the state of Michigan. The Romneys were involved in Mormonism in their states and in the state of Utah.

On January 3, 2013, Tulsi Gabbard became the first Hindu member of Congress, using a copy of the Bhagavad Gita while swearing-in.[163]

2010 ARDA data[]

The Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA) surveyed congregations for their memberships. Churches were asked for their membership numbers. Adjustments were made for those congregations that did not respond and for religious groups that reported only adult membership.[164] ARDA estimates that most of the churches not responding were black Protestant congregations. Significant difference in results from other databases include the lower representation of adherents of 1) all kinds (62.7%), 2) Christians (59.9%), 3) Protestants (less than 36%); and the greater number of unaffiliated (37.3%).

Percentage of religion against average, 2001

Percentage of state populations that identify with a religion rather than "no religion", 2001

| Religious group | Number in year 2010 |

% in year 2010 |

|---|---|---|

| Total US pop year 2010 | 308,745,538 | 100.0% |

| Evangelical Protestant | 50,013,107 | 16.2% |

| Mainline Protestant | 22,568,258 | 7.3% |

| Black Protestant | 4,877,067 | 1.6% |

| Protestant total | 77,458,432 | 25.1% |

| Catholic | 58,934,906 | 19.1% |

| Orthodox | 1,056,535 | 0.3% |

| adherents (unadjusted) | 150,596,792 | 48.8% |

| unclaimed | 158,148,746 | 51.2% |

| other – including Mormon & Christ Scientist | 13,146,919 | 4.3% |

| The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (Mormon, LDS) | 6,144,582 | 2.0% |

| other – excluding Mormon | 7,002,337 | 2.3% |

| Jewish estimate | 6,141,325 | 2.0% |

| Buddhist estimate | 2,000,000 | 0.7% |

| Muslim estimate | 2,600,082 | 0.8% |

| Hindu estimate | 400,000 | 0.4% |

| Source: ARDA[68][165] | ||

ARIS findings regarding self-identification[]

The United States government does not collect religious data in its census. The survey below, the American Religious Identification Survey (ARIS) of 2008, was a random digit-dialed telephone survey of 54,461 American residential households in the contiguous United States. The 1990 sample size was 113,723; 2001 sample size was 50,281.

Adult respondents were asked the open-ended question, "What is your religion, if any?" Interviewers did not prompt or offer a suggested list of potential answers. The religion of the spouse or partner was also asked. If the initial answer was "Protestant" or "Christian" further questions were asked to probe which particular denomination. About one third of the sample was asked more detailed demographic questions.

Religious Self-Identification of the U.S. Adult Population: 1990, 2001, 2008[52]

Figures are not adjusted for refusals to reply; investigators suspect refusals are possibly more representative of "no religion" than any other group.

| Group |

1990 adults x 1,000 |

2001 adults x 1,000 |

2008 adults x 1,000 |

Numerical Change 1990– 2008 as % of 1990 |

1990 % of adults |

2001 % of adults |

2008 % of adults |

change in % of total adults 1990– 2008 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adult population, total | 175,440 | 207,983 | 228,182 | 30.1% | ||||

| Adult population, responded | 171,409 | 196,683 | 216,367 | 26.2% | 97.7% | 94.6% | 94.8% | −2.9% |

| Total Christian | 151,225 | 159,514 | 173,402 | 14.7% | 86.2% | 76.7% | 76.0% | −10.2% |

| Catholic | 46,004 | 50,873 | 57,199 | 24.3% | 26.2% | 24.5% | 25.1% | −1.2% |

| non-Catholic Christian | 105,221 | 108,641 | 116,203 | 10.4% | 60.0% | 52.2% | 50.9% | −9.0% |

| Baptist | 33,964 | 33,820 | 36,148 | 6.4% | 19.4% | 16.3% | 15.8% | −3.5% |

| Mainline Christian | 32,784 | 35,788 | 29,375 | −10.4% | 18.7% | 17.2% | 12.9% | −5.8% |

| Methodist | 14,174 | 14,039 | 11,366 | −19.8% | 8.1% | 6.8% | 5.0% | −3.1% |

| Lutheran | 9,110 | 9,580 | 8,674 | −4.8% | 5.2% | 4.6% | 3.8% | −1.4% |

| Presbyterian | 4,985 | 5,596 | 4,723 | −5.3% | 2.8% | 2.7% | 2.1% | −0.8% |

| Episcopal/Anglican | 3,043 | 3,451 | 2,405 | −21.0% | 1.7% | 1.7% | 1.1% | −0.7% |

| United Church of Christ | 438 | 1,378 | 736 | 68.0% | 0.2% | 0.7% | 0.3% | 0.1% |

| Christian Generic | 25,980 | 22,546 | 32,441 | 24.9% | 14.8% | 10.8% | 14.2% | −0.6% |

| Christian Unspecified | 8,073 | 14,190 | 16,384 | 102.9% | 4.6% | 6.8% | 7.2% | 2.6% |

| Non-denominational Christian | 194 | 2,489 | 8,032 | 4040.2% | 0.1% | 1.2% | 3.5% | 3.4% |

| Protestant – Unspecified | 17,214 | 4,647 | 5,187 | −69.9% | 9.8% | 2.2% | 2.3% | −7.5% |

| Evangelical/Born Again | 546 | 1,088 | 2,154 | 294.5% | 0.3% | 0.5% | 0.9% | 0.6% |

| Pentecostal/Charismatic | 5,647 | 7,831 | 7,948 | 40.7% | 3.2% | 3.8% | 3.5% | 0.3% |

| Pentecostal – Unspecified | 3,116 | 4,407 | 5,416 | 73.8% | 1.8% | 2.1% | 2.4% | 0.6% |

| Assemblies of God | 617 | 1,105 | 810 | 31.3% | 0.4% | 0.5% | 0.4% | 0.0% |

| Church of God | 590 | 943 | 663 | 12.4% | 0.3% | 0.5% | 0.3% | 0.0% |

| Other Protestant Denominations | 4,630 | 5,949 | 7,131 | 54.0% | 2.6% | 2.9% | 3.1% | 0.5% |

| Churches of Christ | 1,769 | 2,593 | 1,921 | 8.6% | 1.0% | 1.2% | 0.8% | −0.2% |

| Jehovah's Witness | 1,381 | 1,331 | 1,914 | 38.6% | 0.8% | 0.6% | 0.8% | 0.1% |

| Seventh-Day Adventist | 668 | 724 | 938 | 40.4% | 0.4% | 0.3% | 0.4% | 0.0% |

| Mormon/Latter Day Saints | 2,487 | 2,697 | 3,158 | 27.0% | 1.4% | 1.3% | 1.4% | 0.0% |

| Total non-Christian religions | 5,853 | 7,740 | 8,796 | 50.3% | 3.3% | 3.7% | 3.9% | 0.5% |

| Jewish | 3,137 | 2,837 | 2,680 | −14.6% | 1.8% | 1.4% | 1.2% | −0.6% |

| Eastern Religions | 687 | 2,020 | 1,961 | 185.4% | 0.4% | 1.0% | 0.9% | 0.5% |

| Buddhist | 404 | 1,082 | 1,189 | 194.3% | 0.2% | 0.5% | 0.5% | 0.3% |

| Muslim | 527 | 1,104 | 1,349 | 156.0% | 0.3% | 0.5% | 0.6% | 0.3% |

| New Religious Movements & Others | 1,296 | 1,770 | 2,804 | 116.4% | 0.7% | 0.9% | 1.2% | 0.5% |

| None/No religion, total | 14,331 | 29,481 | 34,169 | 138.4% | 8.2% | 14.2% | 15.0% | 6.8% |

| Agnostic+Atheist | 1,186 | 1,893 | 3,606 | 204.0% | 0.7% | 0.9% | 1.6% | 0.9% |

| Did Not Know/Refused to reply | 4,031 | 11,300 | 11,815 | 193.1% | 2.3% | 5.4% | 5.2% | 2.9% |

Highlights:[52]

- The ARIS 2008 survey was carried out during February–November 2008 and collected answers from 54,461 respondents who were questioned in English or Spanish.

- The American population self-identifies as predominantly Christian, but Americans are slowly becoming less Christian.

- 86% of American adults identified as Christians in 1990 and 76% in 2008.

- The historic mainline churches and denominations have experienced the steepest declines, while the non-denominational Christian identity has been trending upward, particularly since 2001.

- The challenge to Christianity in the U.S. does not come from other religions but rather from a rejection of all forms of organized religion.

- 34% of American adults considered themselves "Born Again or Evangelical Christians" in 2008.

- The U.S. population continues to show signs of becoming less religious, with one out of every seven Americans failing to indicate a religious identity in 2008.

- The "Nones" (no stated religious preference, atheist, or agnostic) continue to grow, though at a much slower pace than in the 1990s, from 8.2% in 1990, to 14.1% in 2001, to 15.0% in 2008.

- Asian Americans are substantially more likely to indicate no religious identity than other racial or ethnic groups.

- One sign of the lack of attachment of Americans to religion is that 27% do not expect a religious funeral at their death.

- Based on their stated beliefs rather than their religious identification in 2008, 70% of Americans believe in a personal God, roughly 12% of Americans are atheist (no God) or agnostic (unknowable or unsure), and another 12% are deistic (a higher power but no personal God).

- America's religious geography has been transformed since 1990. Religious switching along with Hispanic immigration has significantly changed the religious profile of some states and regions. Between 1990 and 2008, the Catholic population proportion of the New England states fell from 50% to 36% and in New York fell from 44% to 37%, while it rose in California from 29% to 37% and in Texas from 23% to 32%.

- Overall the 1990–2008 ARIS time series shows that changes in religious self-identification in the first decade of the 21st century have been moderate in comparison to the 1990s, which was a period of significant shifts in the religious composition of the United States.

Ethnicity[]

The table below shows the religious affiliations among the ethnicities in the United States, according to the Pew Forum 2014 survey.[63] People of Black ethnicity were most likely to be part of a formal religion, with 85% percent being Christians. Protestant denominations make up the majority of the Christians in the ethnicities.

| Religion | Non-Hispanic White |

Black | Hispanic | Other/mixed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Christian | 70% | 79% | 77% | 49% |

| Protestant | 48% | 71% | 26% | 33% |

| Catholic | 19% | 5% | 48% | 13% |

| Mormon | 2% | <0.5% | 1% | 1% |

| Jehovah's Witness | <0.5% | 2% | 1% | 1% |

| Orthodox | 1% | <0.5% | <0.5% | 1% |

| Other | <0.5% | 1% | <0.5% | 1% |

| Non-Christian faiths | 5% | 3% | 2% | 21% |

| Jewish | 3% | <0.5% | 1% | 1% |

| Muslim | <0.5% | 2% | <0.5% | 3% |

| Buddhist | <0.5% | <0.5% | 1% | 4% |

| Hindu | <0.5% | <0.5% | <0.5% | 8% |

| Other world religions | <0.5% | <0.5% | <0.5% | 2% |

| Other faiths | 2% | 1% | 1% | 2% |

| Unaffiliated (including atheist and agnostic) | 24% | 18% | 20% | 29% |

See also[]

- American civil religion

- Freedom of religion in the United States

- Historical religious demographics of the United States

- List of religious movements that began in the United States

- List of U.S. states and territories by religiosity

- Relationship between religion and science

- Religion in United States prisons

- School prayer#United States

- Separation of church and state in the United States

References[]

- ^ a b c d e f g h Inc., Gallup,. "Five Key Findings on Religion in the U.S." (in en-us). Gallup.com. http://www.gallup.com/poll/200186/five-key-findings-religion.aspx.

- ^ a b "Among Wealthy Nations U.S. Stands Alone in its Embrace of Religion". Pew Global Attitudes Project. http://pewglobal.org/reports/display.php?ReportID=167. Retrieved 2007-01-01.

- ^ Newport, Frank (2016-02-04). "New Hampshire Now Least Religious State in U.S.". Gallup. http://www.gallup.com/poll/189038/new-hampshire-least-religious-state.aspx. Retrieved 2016-08-03.

- ^ a b https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/aq.html CIA World Factbook. American Samoa. Retrieved September 7, 2018. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "AmericanSamoa1" defined multiple times with different content - ^ Sydney Ahlstrom, A Religious History of the American People (Yale UP, 2nd ed. 2004) ISBN 0-300-10012-4

- ^ Kevin M. Schultz, and Paul Harvey, "Everywhere and Nowhere: Recent Trends in American Religious History and Historiography", Journal of the American Academy of Religion, March 2010, Vol. 78 Issue 1, pp. 129–162

- ^ See: English Civil War, Glorious Revolution, Restoration (England) and Nonconformists

- ^ David E. Swift (1989). Black Prophets of Justice: Activist Clergy Before the Civil War. LSU Press. p. 180. https://books.google.com/books?id=bUVNttmT13AC&pg=PA180.

- ^ The treaty is online

- ^ Tri-Faith America: How Catholics and Jews Held Postwar America to Its Protestant Promise by Kevin M. Schultz, p. 9

- ^ Obligations of Citizenship and Demands of Faith: Religious Accommodation in Pluralist Democracies by Nancy L. Rosenblum, Princeton University Press, 2000 – 438, p. 156

- ^ The Protestant Voice in American Pluralism by Martin E. Marty, chapter 1

- ^ "10 facts about religion in America". August 27, 2015. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/08/27/10-facts-about-religion-in-america/. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- ^ Barnstone, Aliki; Manson, Michael Tomasek; Singley, Carol J. (August 27, 1997). "The Calvinist Roots of the Modern Era". UPNE. https://books.google.com/books?id=_UJXV7HYlaQC&pg=PR13&lpg=PR13. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- ^ Holmes, David L. (May 1, 2006). "The Faiths of the Founding Fathers". Oxford University Press, USA. https://books.google.com/books?id=Ux9nDAAAQBAJ&pg=PA13&dq=united+states+founded+on+calvinism&hl=pl&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjB5ZD0vvXUAhVCAZoKHQ6ZCecQ6AEIaDAJ#v=onepage&q=united+states+founded+on+calvinism&f=false. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- ^ "Calvinism: The Spiritual Foundation of America". January 20, 2016. https://www.geopolitica.ru/en/article/calvinism-spiritual-foundation-america.

- ^ National motto

- ^ a b "U.S. on the History of "In God We Trust"". United States Department of the Treasury. http://www.treasury.gov/about/education/Pages/in-god-we-trust.aspx. Retrieved 2009-04-22.

- ^ United States Public Law 84-851, United States Public Law 84-851.

- ^ Gilleland, Don (January 3, 2013). "50 years of change". Florida Today (Melbourne, Florida): pp. 9A. http://www.floridatoday.com/article/20130103/COLUMNISTS0205/301030003/Guest-column-50-years-change.

- ^ a b c d e f g Template:Cite publication

- ^ Encylclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/place/Massachusetts-Bay-Colony

- ^ Feldman, Noah (2005). Divided by God. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, p. 10 ("For the first time in recorded history, they designed a government with no established religion at all.")

- ^ Marsden, George M. 1990. Religion and American Culture. Orlando: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, pp. 45–46.

- ^ a b c d e f "Religion Census Newsletter". Association of Statisticians of American Religious Bodies. March 2017. http://www.rcms2010.org/images/NL201703LargestNonXnMail.pdf.

- ^ "News from the National Council of Churches". Ncccusa.org. http://www.ncccusa.org/news/120209yearbook2012.html.

- ^ Gaustad 1962

- ^ "Annual of the 2007 Southern Baptist Convention" (PDF). http://www.sbcec.net/bor/2007/2007SBCAnnual.pdf. Retrieved 2012-12-29.

- ^ The figures for this 2007 abstract are based on surveies for 1990 and 2001 from the Graduate School and University Center at the City University of New York. Kosmin, Barry A.; Egon Mayer; Ariela Keysar (2001). "American Religious Identification Survey". City University of New York.; Graduate School and University Center. Archived from the original on June 14, 2007. https://web.archive.org/web/20070614124201/http://www.trincoll.edu/NR/rdonlyres/AFCEF53A-8DAB-4CD9-A892-5453E336D35D/0/NEWARISrevised121901b.pdf. Retrieved 2007-04-04.

- ^ (2015) "Believers in Christ from a Muslim Background: A Global Census". IJRR 11. Retrieved on 20 November 2015.

- ^ Why Are Millions of Muslims Becoming Christian?

- ^ McKinney, William. "Mainline Protestantism 2000." Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Vol. 558, Americans and Religions in the Twenty-First Century (July, 1998), pp. 57-66.

- ^ Harriet Zuckerman, Scientific Elite: Nobel Laureates in the United States New York, The Free Pres, 1977, p.68: Protestants turn up among the American-reared laureates in slightly greater proportion to their numbers in the general population. Thus 72 percent of the seventy-one laureates but about two thirds of the American population were reared in one or another Protestant denomination-)

- ^ a b c d e f B. Drummond Ayres, Jr. (2011-12-19). "The Episcopalians: An American Elite with Roots Going Back to Jamestown". New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1981/04/28/us/the-episcopalians-an-american-elite-with-roots-going-back-to-jamestown.html. Retrieved 2012-08-17.

- ^ Hacker, Andrew (1957). "Liberal Democracy and Social Control". American Political Science Review 51 (4): 1009–1026 [p. 1011].

- ^ Ron Chernow, Titan (New York: Random, 1998) 50.

- ^ Irving Lewis Allen, "WASP—From Sociological Concept to Epithet," Ethnicity, 1975 154+

- ^ http://www.pewforum.org/2015/05/12/americas-changing-religious-landscape/

- ^ http://www.pewforum.org See: "How income varies among US religious groups." 19% of Catholics (19% of 75 million, i.e., over 14 million) "live in households with incomes of at least 100,000."

- ^ "The Harvard Guide: The Early History of Harvard University". News.harvard.edu. Archived from the original on July 22, 2010. https://web.archive.org/web/20100722203532/http://www.news.harvard.edu/guide/intro/index.html. Retrieved 2010-08-29.

- ^ "Increase Mather". http://college.hmco.com/history/readerscomp/rcah/html/ah_057300_matherincrea.htm., Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Princeton University Office of Communications. "Princeton in the American Revolution". http://www.princeton.edu/pr/facts/revolution.html. Retrieved 2011-05-24. The original Trustees of Princeton University "were acting in behalf of the evangelical or New Light wing of the Presbyterian Church, but the college had no legal or constitutional identification with that denomination. Its doors were to be open to all students, 'any different sentiments in religion notwithstanding.'"

- ^ McCaughey, Robert (2003). Stand, Columbia: A History of Columbia University in the City of New York. New York, New York: Columbia University Press. p. 1. ISBN 0231130082.

- ^ Childs, Francis Lane (December 1957). "A Dartmouth History Lesson for Freshman". Dartmouth Alumni Magazine. http://www.dartmouth.edu/~library/rauner/dartmouth/dartmouth_history.html. Retrieved February 12, 2007.

- ^ W.L. Kingsley et al., "The College and the Church," New Englander and Yale Review 11 (Feb 1858): 600. accessed 2010-6-16 Note: Middlebury is considered the first "operating" college in Vermont as it was the first to hold classes in Nov 1800. It issued the first Vermont degree in 1802; UVM followed in 1804.

- ^ James Davison Hunter (March 31, 2010). To Change the World: The Irony, Tragedy, and Possibility of Christianity in the Late Modern World. Oxford UP. p. 85. https://books.google.com/books?id=NYpEwnnIIqAC&pg=PA85.

- ^ Sydney E. Ahlstrom, A religious history of the American people (1976) pp. 121-59 .

- ^ FitzGerald 2007, p. 269-279.

- ^ Alexei D. Krindatch, ed., Atlas of American Orthodox Christian Churches (Holy Cross Orthodox Press, 2011) online.

- ^ "Largest Latter-day Saint Communities (Mormon/Church of Jesus Christ Statistics)". adherents.com. 2005-04-12. http://www.adherents.com/largecom/com_lds.html.

- ^ "American Religious Identification Survey". Exhibit 15. The Graduate Center, City University of New York. http://www.gc.cuny.edu/faculty/research_briefs/aris/key_findings.htm. Retrieved 2006-11-24.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Barry A. Kosmin and Ariela Keysar (2009). "American Religious Identification Survey (ARIS) 2008" (PDF). Hartford, Connecticut, US: Trinity College. https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/metro/documents/aris030609.pdf. Retrieved 2009-04-01.

- ^ "Barna Survey Examines Changes in Worldview Among Christians over the Past 13 Years". The Barna Group. 2009-03-06. Archived from the original on March 12, 2009. https://web.archive.org/web/20090312095809/http://www.barna.org/barna-update/article/12-faithspirituality/252-barna-survey-examines-changes-in-worldview-among-christians-over-the-past-13-years. Retrieved 2009-06-26.

- ^ a b c "America's Changing Religious Landscape". Pew Research Center: Religion & Public Life. May 12, 2015. http://www.pewforum.org/2015/05/12/americas-changing-religious-landscape/.

- ^ (PDF) US Religious Landscape Survey: Diverse and Dynamic, The Pew Forum, February 2008, p. 85, http://religions.pewforum.org/pdf/report-religious-landscape-study-full.pdf, retrieved 2012-09-17

- ^ "The most and least educated U.S. religious group". Pew Research Center. 2016-10-16. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/11/04/the-most-and-least-educated-u-s-religious-groups/.

- ^ Leonhardt, David (2011-05-13). "Faith, Education and Income". The New York Times. https://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/05/13/faith-education-and-income/. Retrieved May 13, 2011.

- ^ "How income varies among U.S. religious groups". Pew Research Center. 2016-10-16. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/10/11/how-income-varies-among-u-s-religious-groups/.

- ^ "The most and least educated U.S. religious groups," and "how income varies among U.S. religious groups" in Pew Research Center: 26% and 19% of 75 million Catholics are college graduates and high income earners, respectively. No religious community can match those numbers

- ^ Taylor, Humphrey (October 15, 2003), "While Most Americans Believe in God, Only 36% Attend a Religious Service Once a Month or More Often", The Harris Poll #59, HarrisInteractive.com, Harris Interactive, http://www.harrisinteractive.com/vault/Harris-Interactive-Poll-Research-While-Most-Americans-Believe-in-God-Only-36-pct-A-2003-10.pdf, retrieved 2014-02-18

- ^ Kosmin, Mayer & Keysar (2001-12-19). "American Identification Survey, 2001" (PDF). The Graduate Center of the City University of New York New York. pp. 8–9. http://www.gc.cuny.edu/CUNY_GC/media/CUNY-Graduate-Center/PDF/ARIS/ARIS-PDF-version.pdf?ext=.pdf. Retrieved 2012-11-24.

- ^ "Jewish Community Study of New York" (PDF). United Jewish Appeal-Federation of New York. 2002. Archived from the original on June 14, 2007. https://web.archive.org/web/20070614001800/http://www.ujafedny.org/atf/cf/%7BAD848866-09C4-482C-9277-51A5D9CD6246%7D/JCommStudyIntro.pdf. Retrieved 2008-03-22.

- ^ a b c "America's Changing Religious Landscape". Pew Research Center: Religion & Public Life. May 12, 2015. http://www.pewforum.org/2015/05/12/americas-changing-religious-landscape/.

- ^ "CIA Fact Book". CIA World Fact Book. 2002. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/us.html. Retrieved 2007-12-30.

- ^ Jack Wertheimer (2002). Jews in the Center: Conservative Synagogues and Their Members. Rutgers University Press. p. 68. https://books.google.com/books?id=U_nEoAZ6ffgC&pg=PA68.

- ^ Adele Reinhartz (2014). "The Vanishing Jews of Antiquity". Los Angeles Review of Books. http://marginalia.lareviewofbooks.org/vanishing-jews-antiquity-adele-reinhartz/.