| Regions with significant populations | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greater Toronto Area, Hamilton, Waterloo Region, Windsor, Shelburne (Ontario), Ottawa–Gatineau, Greater Montreal, Shelburne (Nova Scotia), Yarmouth, Halifax, Brooks, Calgary, Edmonton, Winnipeg | |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Languages | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

Canadian English • Canadian French • Caribbean English • Haitian Creole • African languages | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

Predominantly Christianity; minority Islam, other faiths | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Related ethnic groups | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

Afro-Caribbeans • African Americans |

Black Canadians is a designation used for people of Black African descent, who are citizens or permanent residents of Canada.[1][2] The majority of Black Canadians are of Caribbean origin, though the population also consists of African American immigrants and their descendants (including Black Nova Scotians), as well as many African immigrants.[3]

Black Canadians often draw a distinction between those of Afro-Caribbean ancestry and those of other African roots. The term African Canadian is occasionally used by some Black Canadians who trace their heritage to the first slaves brought by British and French colonists to the North American mainland.[2] Promised freedom by the British during the American Revolutionary War, thousands of Black Loyalists were resettled by the Crown in Canada afterward, such as Thomas Peters. In addition, an estimated ten to thirty thousand fugitive slaves reached freedom in Canada from the Southern United States during the antebellum years, aided by people along the Underground Railroad.

Many Black people of Caribbean origin in Canada reject the term African Canadian as an elision of the uniquely Caribbean aspects of their heritage,[4] and instead identify as Caribbean Canadian.[4] Unlike in the United States, where African American has become a widely used term, in Canada controversies associated with distinguishing African or Caribbean heritage have resulted in the term "Black Canadian" being widely accepted there.[5]

Black Canadians have contributed to many areas of Canadian culture.[6] Many of the first visible minorities to hold high public offices have been Black, including Michaëlle Jean, Donald Oliver, Stanley G. Grizzle, Rosemary Brown and Lincoln Alexander, in turn opening the door for other minorities.[7] Black Canadians form the third-largest visible minority group in Canada, after South Asian and Chinese Canadians.[8]

Population[]

According to the 2006 Census by Statistics Canada, 783,795 Canadians identified as black, constituting 2.5% of the entire Canadian population.[8] Of the black population, 11% identified as mixed-race of "white and black".[9] The five most black-populated provinces in 2006 were Ontario, Quebec, Alberta, British Columbia, and Nova Scotia.[8] The ten most black-populated census metropolitan areas were Toronto, Montreal, Ottawa, Calgary, Vancouver, Edmonton, Hamilton, Winnipeg, Halifax, and Oshawa.[10] Preston, in the Halifax area, is the community with the highest percentage of black people, with 69.4%; it was a settlement where the Crown provided land to Black Loyalists after the American Revolution.[11]

According to the 2011 Census, a total of 945,665 Black Canadians were counted, making up 2.9% of Canada's population.[12] In the 2016 Census, the black population totalled 1,198,540, encompassing 3.5% of the country's population.[13]

Demographics and Census issues[]

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1871 | 21,500 | — |

| 1881 | 21,400 | −0.5% |

| 1901 | 17,500 | −18.2% |

| 1911 | 16,900 | −3.4% |

| 1921 | 18,300 | +8.3% |

| 1931 | 19,500 | +6.6% |

| 1941 | 22,200 | +13.8% |

| 1951 | 18,000 | −18.9% |

| 1961 | 32,100 | +78.3% |

| 1971 | 34,400 | +7.2% |

| 1981 | 239,500 | +596.2% |

| 1991 | 504,300 | +110.6% |

| 2001 | 662,200 | +31.3% |

| 2011 | 945,665 | +42.8% |

| 2016 | 1,198,540 | +26.7% |

| Census data[12][14][8][13] | ||

At times, it has been claimed that Black Canadians have been significantly undercounted in census data. Writer George Elliott Clarke has cited a McGill University study which found that fully 43% of all Black Canadians were not counted as black in the 1991 Canadian census, because they had identified on census forms as British, French or other cultural identities which were not included in the census group of Black cultures.[15]

Although subsequent censuses have reported the population of Black Canadians to be much more consistent with the McGill study's revised 1991 estimate than with the official 1991 census data, no recent study has been conducted to determine whether some Black Canadians are still substantially missed by the self-identification method.

Terminology[]

One of the ongoing controversies in the Black Canadian community revolves around appropriate terminologies. Many Canadians of Afro-Caribbean origin strongly object to the term "African Canadian", as it obscures their own culture and history, and this partially accounts for the term's less prevalent use in Canada, compared to the consensus "African American" south of the border.

Black Nova Scotians, a more distinct cultural group, of whom some can trace their Canadian ancestry back to the 1700s, use both terms, African Canadian and Black Canadian. For example, there is an Office of African Nova Scotian Affairs and a Black Cultural Centre for Nova Scotia.

"Caribbean Canadian" is often used to refer to Black Canadians of Caribbean heritage, although this usage can also be controversial because the Caribbean is not populated only by people of African origin, but also includes large groups of Indo-Caribbeans, Chinese Caribbeans, European Caribbeans, Syrian or Lebanese Caribbeans, Latinos and Amerindians. The term "West Indian" is often used by those of Caribbean ancestry, although the term is more of a cultural description than a racial one, and can equally be applied to groups of many different racial and ethnic backgrounds. The term "Afro-Caribbean-Canadian" is occasionally used in response to this controversy, although as of 2024, this term is still not widely seen in common usage.

More specific national terms such as "Jamaican Canadian", "Haitian Canadian" or "Ghanaian Canadian" are also used. As of 2024, however, there is no widely used alternative to "Black Canadian" that is accepted by the Afro-Caribbean population, those of more recent African extraction, and descendants of immigrants from the United States as an umbrella term for the whole group.[5]

One increasingly common practice, seen in academic usage and in the names and mission statements of some Black Canadian cultural and social organizations but not yet in universal nationwide usage, is to always make reference to both the African and Caribbean communities.[16] For example, one key health organization dedicated to HIV/AIDS education and prevention in the Black Canadian community is now named the African and Caribbean Council on HIV/AIDS in Ontario, the Toronto publication Pride bills itself as an "African-Canadian and Caribbean-Canadian news magazine", and G98.7, a Black-oriented community radio station in Toronto, was initially branded as Caribbean African Radio Network.[17]

In French, the terms noirs canadiens or afro-canadiens are used. Nègre ("Negro") is considered derogatory; in 2015 five placenames containing Nègre were changed.[18]

History[]

One of the more noted aspects of Black Canadian history is that while the majority of African Americans trace their presence in the United States through the history of slavery, the Black presence in Canada is rooted almost entirely in voluntary immigration.[19] Despite the various dynamics that may complicate the personal and cultural interrelationships between descendants of the Black Loyalists in Nova Scotia, descendants of former American slaves who viewed Canada as the promise of freedom at the end of the Underground Railroad, and more recent immigrants from the Caribbean or Africa, one common element that unites all of these groups is that they are in Canada because they or their ancestors actively chose of their own free will to settle there.[4]

First black people in Canada[]

Mathieu de Costa, the first recorded free black person to arrive in Canada.

The first recorded black person to set foot on land now known as Canada was a free man named Mathieu de Costa. Travelling with navigator Samuel de Champlain, de Costa arrived in Nova Scotia some time between 1603 and 1608 as a translator for the French explorer Pierre Dugua, Sieur de Monts. The first known black person to live in what would become Canada was a slave from Madagascar named Olivier Le Jeune, who may have been of partial Malay ancestry. As a group, black people arrived in Canada in several waves. The first of these came as free persons serving in the French Army and Navy, though some were enslaved or indentured servants. About 1, 000 slaves were brought to New France in the 17th and 18th centuries.[20] By the time of the British conquest of New France in 1759-1760, there were about 3, 604 slaves of all races in New France, of whom 1, 132 were black.[21] The majority of the slaves lived in Montreal, the largest city in New France and the center of the lucrative fur trade.[22] Marie-Joseph Angélique, a black slave from Portugal who arrived in New France in 1725 was accused of setting the fire that burned down most of Montreal on 10 April 1734, for which she was executed.

African Americans during the American Revolution[]

Anderson Ruffin Abbott, the first Black Canadian to be a licensed physician, participated in the American Civil War and attended the deathbed of Abraham Lincoln.

At the time of the American Revolution, inhabitants of the United States had to decide where their future lay. Those loyal to the British Crown were called United Empire Loyalists and came north. Many White American Loyalists brought their African-American slaves with them, numbering approximately 2,500 individuals. During the war, the British had promised freedom to slaves who left rebel masters and worked for them; this was announced in Virginia through Lord Dunmore's Proclamation. Slaves also escaped to British lines in New York City and Charleston, and their forces evacuated thousands after the war. They transported 3,000 to Nova Scotia.[23][24]

This latter group was largely made up of merchants and labourers, and many set up home in Birchtown near Shelburne. Some settled in New Brunswick. Both groups suffered from discriminatory treatment by white settlers and prominent landowners who still held slaves. Some of the refugees had been free black people prior to the war and fled with the other refugees to Nova Scotia, relying on British promises of equality. Under pressure of the new refugees, the city of Saint John amended its charter in 1785 specifically to exclude black people from practising a trade, selling goods, fishing in the harbour, or becoming freemen; these provisions stood until 1870, although by then they were largely ignored.[25]

In 1782, the first race riot in North America took place in Shelburne; white veterans attacked African-American settlers who were getting work that the former soldiers thought they should have. Due to the failure of the British government to support the settlement, the harsh weather, and discrimination on the part of white colonists, 1,192 Black Loyalist men, women and children left Nova Scotia for West Africa on 15 January 1792. They settled in what is now Sierra Leone, where they became the original settlers of Freetown. They, along with other groups of free transplanted people such as the Black Poor from England, became what is now the Sierra Leone Creole people, also known as the Krio.

Although difficult to estimate due to the failure to differentiate slave and free Black populations, it is estimated that by 1784 there were around 40 Black slaves within Montreal, compared to around 304 slaves within the Province of Quebec.[26] By 1799, vital records note 75 entries regarding Black Canadians, a number that doubled by 1809.[26]

Maroons from the Caribbean[]

On 26 June 1796, Jamaican Maroons, numbering 543 men, women and children, were deported on board the three ships Dover, Mary and Anne from Jamaica, after being defeated in an uprising against the British colonial government. Their initial destination was Lower Canada, but on 21 and 23 July, the ships arrived in Nova Scotia. At this time Halifax was undergoing a major construction boom initiated by Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn's efforts to modernize the city's defences. The many building projects had created a labour shortage. Edward was impressed by the Maroons and immediately put them to work at the Citadel in Halifax, Government House, and other defence works throughout the city.

Funds had been provided by the Government of Jamaica to aid in the resettlement of the Maroons in Canada.[27] Five thousand acres were purchased at Preston, Nova Scotia, at a cost of £3000. Small farm lots were provided to the Maroons and they attempted to farm the infertile land. Like the former tenants, they found the land at Preston to be unproductive; as a result they had little success. The Maroons also found farming in Nova Scotia difficult because the climate would not allow cultivation of familiar food crops, such as bananas, yams, pineapples or cocoa. Small numbers of Maroons relocated from Preston to Boydville for better farming land. The British Lieutenant Governor Sir John Wentworth made an effort to change the Maroons' culture and beliefs by introducing them to Christianity. From the monies provided by the Jamaican Government, Wentworth procured an annual stipend of £240 for the support of a school and religious education.[28] The Maroons were not interested in converting from their own religion to Christianity. Strong-willed and opinionated people, they refused to work for less money than was paid to white workers.

After suffering through the harsh winter of 1796–97, Wentworth reported the Maroons expressed a desire that "they wish to be sent to India or somewhere in the east, to be landed with arms in some country with a climate like that they left, where they may take possession with a strong hand".[28]:260 The British Government and Wentworth opened discussions with the Sierra Leone Company in 1799 to send the Maroons to Sierra Leone. The Jamaican Government had in 1796 initially planned to send the Maroons to Sierra Leone but the Sierra Leone Company rejected the idea. The initial reaction in 1799 was the same, but the Company was eventually persuaded to accept the Maroon settlers. On 6 August 1800 the Maroons departed Halifax, arriving on 1 October at Freetown, Sierra Leone.[28][29]

Upon their arrival in West Africa in 1800, they were used to quell an uprising among the black settlers from Nova Scotia and London. After eight years, they were unhappy with their treatment by the Sierra Reynolds Company.

Abolition of slavery[]

Monument in Pictou, Nova Scotia dedicated to abolitionist James Drummond MacGregor, who helped free Black Nova Scotian slaves

The Canadian climate made it uneconomic to keep slaves year-round,[30] unlike the plantation agriculture practised in the southern United States and Caribbean. Slavery within the colonial economy became increasingly rare. Not all owners were white. Some were half-white. For example, the powerful Mohawk leader Joseph Brant bought an African American named Sophia Burthen Pooley, whom he kept for about 12 years before selling her for $100.[31][32]

In 1772, prior to the American Revolution, Britain outlawed the slave trade in the British Isles followed by the Knight v. Wedderburn decision in Scotland in 1778. This decision, in turn, influenced the colony of Nova Scotia. In 1788, abolitionist James Drummond MacGregor from Pictou published the first anti-slavery literature in Canada and began purchasing slaves' freedom and chastising his colleagues in the Presbyterian church who owned slaves.[33]

In 1790 John Burbidge freed his slaves. Led by Richard John Uniacke, in 1787, 1789 and again on January 11, 1808, the Nova Scotian legislature refused to legalize slavery.[34][35] Two chief justices, Thomas Andrew Lumisden Strange (1790–1796) and Sampson Salter Blowers (1797–1832) were instrumental in freeing slaves from their owners in Nova Scotia.[36][37] These justices were held in high regard in the colony.

In 1793, John Graves Simcoe, the first Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada, attempted to abolish slavery. That same year, the new Legislative Assembly became the first entity in the British Empire to restrict slavery, confirming existing ownership but allowing for anyone born to a female slave after that date to be freed at the age of 25.[38] Slavery was all but abolished throughout the other British North American colonies by 1800. The Slave Trade Act outlawed the slave trade in the British Empire in 1807 and the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 outlawed slave-holding altogether in the colonies (except for India). This made Canada an attractive destination for many refugees fleeing slavery in the United States, such as minister Boston King.

War of 1812[]

The next major migration of black people occurred between 1813 and 1815. Refugees from the War of 1812, primarily from the Chesapeake Bay and Georgia Sea Islands, fled the United States to settle in Hammonds Plains, Beechville, Lucasville, North Preston, East Preston, Africville and Elm Hill, New Brunswick. An April 1814 proclamation of Black freedom and settlement by British Vice-Admiral Alexander Cochrane led to an exodus of around 3,500 Black Americans by 1818.[39] The settlement of the refugees was initially seen as a means of creating prosperous agricultural communities; however, poor economic conditions following the war coupled with the granting of infertile farmland to refugees caused economic hardship.[39] Social integration proved difficult in the early years, as the prevalence of enslaved Africans in the Maritimes caused the newly freed Black Canadians to be viewed on the same level of the enslaved.[39] Politically, the black Loyalist communities in both Nova Scotia and Upper Canada were characterized by what the historian James Walker called "a tradition of intense loyalty to Britain" for granting them freedom and Canadian blacks tended to be active in the militia, especially in Upper Canada during the War of 1812 as the possibility of an American victory would also mean the possibility of their re-enslavement.[40] Militarily, a Black Loyalist named Richard Pierpoint, who was born about 1744 in Senegal and who had settled near present-day St. Catharines, Ontario, offered to organize a Corps of Men of Colour to support the British war effort. This was refused but a white officer raised a small black corps.[23] This "Coloured Corps" fought at Queenston Heights and the siege of Fort George, defending what would become Canada from the invading American army.[23] Many of the refugees from America would later serve with distinction during the war in matters both strictly military, along with the use of freed slaves in assisting in the further liberation of African Americans slaves.[39]

The Underground Railroad[]

There is a sizable community of Black Canadians in Nova Scotia[24] and Southern Ontario who trace their ancestry to African-American slaves who used the Underground Railroad to flee from the United States, seeking refuge and freedom in Canada. From the late 1820s, through the time that the United Kingdom itself forbade slavery in 1833, until the American Civil War began in 1861, the Underground Railroad brought tens of thousands of fugitive slaves to Canada. In 1819, Sir John Robinson, the Attorney-General of Upper Canada, ruled: "Since freedom of the person is the most important civil right protected by the law of England...the negroes are entitled to personal freedom through residence in Upper Canada and any attempt to infringe their rights will be resisted in the courts".[41] After Robinson's ruling in 1819, judges in Upper Canada refused American requests to extradite run-away slaves who reached Upper Canada under the grounds "every man is free who reaches British ground".[42] One song popular with African-Americans called the Song of the Free had the lyrics: "I'm on my way to Canada, That cold and distant land, The dire effects of slavery, I can no longer stand, Farewell, old master, Don't come after me, I'm on my way to Canada, Where colored men are free!".[43]

In 1850, the United States Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act, which gave bounty hunters the right to recapture run-away slaves anywhere in the United States and ordered all federal, state and municipal law enforcement to co-operate with the bounty hunters in seizing run-away slaves.[44] Since the Fugitive Slave Act stripped accused fugitive slaves of any legal rights such as the right to testify in court that they were not run-away slaves, cases of freemen and freewomen being kidnapped off the streets to be sold into slavery become common.[45] The U.S justice system in the 1850s was hostile to black people, and little inclined to champion their rights. In 1857, in the Dred Scott v. Sandford decision, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that black Americans were not and never could be U.S. citizens under any conditions, a ruling that appeared to suggest that laws prohibiting slavery in the northern states were unconstitutional. As a result of the Fugitive Slave Act and legal rulings to expand slavery in the United States, many free blacks living in the United States chose to seek sanctuary in Canada with one newspaper in 1850 mentioning that a group of blacks working for a Pittsburgh hotel had armed themselves with handguns before heading for Canada saying they were "...determined to die rather be captured".[46] The Toronto Colonist newspaper on 17 June 1852 noted that almost every ship or boat coming into Toronto harbor from the American side of Lake Ontario seemed to be carrying a run-away slave.[47]

Rev. Samuel Ringgold Ward, c.1855. Ward had been forced to flee to Canada West in 1851 to escape charges of violating the Fugitive Slave Act by helping a run-away slave escape to Canada.

During the course of one week in June 1854, 23 run-away slaves evaded the U.S border patrols to cross the Detroit river to freedom in Windsor while 43 free people also crossed over to Windsor out of the fear of the bounty hunters.[48] The American-born Canadian historian Daniel G. Hill wrote this week in June 1854 appeared to be typical of the black exodus to Canada.[49] Public opinion tended to be on the side of run-away slaves and against the slavers. On 26 February 1851, the Toronto chapter of the Anti-Slavery Society was founded with what was described by the Globe newspaper as "the largest and most enthusiastic meeting we have ever seen in Toronto" that issued the resolution: "slavery is an outrage on the laws of humanity and its continued practice demands the best exertions for its extinction".[50] The same meeting committed its members to help the many "houseless and homeless victims of slavery flying to our soil".[51] The Congregationalist minister, the Reverend Samuel Ringgold Ward of New York, who had been born into slavery in Maryland, wrote about Canada West (modern Ontario) that: "Toronto is somewhat peculiar in many ways, anti-slavery is more popular there than in any city I know save Syracuse...I had good audiences in the towns of Vaughan, Markham, Pickering and in the village of Newmarket. Anti-slavery feeling is spreading and increasing in all these places. The public mind literally thirsts for the truth, and honest listeners and anxious inquirers will travel many miles, crowd our country chapels, and remain for hours eagerly and patiently seeking the light".[52] Ward himself had been forced to flee to Canada West in 1851 for his role in the Jerry Rescue, leading to his indictment for violating the Fugitive Slave Act. Despite the support to run-away slaves, blacks in Canada West, which become Ontario in 1867, were confided to segregated schools.[53]

American bounty-hunters who crossed into Canada to kidnap black people to sell into slavery were prosecuted for kidnapping if apprehended by the authorities.[54] In 1857, an attempt by two American bounty hunters, T.G. James and John Wells, to kidnap Joseph Alexander, a 20-year old run-away slave from New Orleans living in Chatham, was foiled when a large crowd of black people surrounded the bounty hunters as they were leaving the Royal Exchange Hotel in Chatham with Alexander who had gone there to confront them.[55] Found on one of the bounty hunters was a letter from Alexander's former master describing him as a slave of "saucy" disposition who had smashed the master's carriage and freed a span of his horses before running away, adding that he was keen to get Alexander back so he could castrate him.[56] Castration was the normal punishment for a male run-away slave. Alexander gave a speech to the assembled by-standers watching the confrontation denouncing life in the "slave pens" of New Orleans as extremely dehumanizing and stated he would rather die than return to living as a slave.[57] Alexander described life in the "slave pens" as a regime of daily whippings, beatings and rapes designed to cow the slaves into a state of utter submission. The confrontation ended with Alexander being freed and the crowd marching Wells and James to the railroad station, warning them to never return to Chatham.[58]

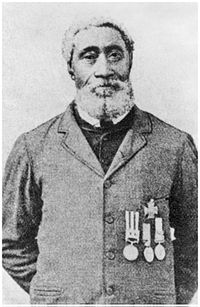

William Hall of Nova Scotia was the first black man to win the Victoria Cross

The refugee slaves who settled in Canada did so primarily in South Western Ontario, with significant concentrations being found in Amherstburg, Colchester, Chatham, Windsor, and Sandwich. Run-away slaves tended to concentrate, partly to provide mutual support, party because of prejudices, and partly out of the fear of American bounty hunters crossing the border.[59] The run-away slaves usually arrived destitute and without any assets, had to work as laborers for others until they could save up enough money to buy their own farms.[60] These settlements acted as centres of abolitionist thought, with Chatham being the location of abolitionist John Brown's constitutional convention which preceded the later raid on Harper's Ferry.[61] While the first newspaper published by a black woman was founded in North Buxton by the free Black Mary Ann Shadd which pressed for Black emigration to Canada as the best option for fleeing African Americans.[61] The settlement of Elgin was formed in 1849 with the royal assent of Governor-General of the time James Bruce as a settlement for Black Canadians and escaped slaves based upon social welfare and the prevention of moral decay among the Black community there. Led by the Elgin Association and preacher William King, the settlement flourished as a model of a successful predominantly African settlement which held close to 200 families by 1859.[62]

From the abolition of slavery in the British empire in 1834, any black man was born a British subject or become a British subject was allowed to vote and run for office, provided that they owned taxable property.[63] The property requirement on voting in Canada was not ended until 1920.[64] Black Canadian women like all other Canadian women were not granted the right to vote until partially in 1917 ( when wives, daughters, sisters and mothers of servicemen were granted the right to vote) and fully in 1918 (when all women were granted the right to vote).[65] In 1850, Canadian black women together with all other women were granted the right to vote for school trustees, which was the limit of female voting rights in Canada West.[66] In 1848, in Colchester county in Canada West, white men prevented black men from voting in the municipal elections, but following complaints in the courts, a judge ruled that black voters could not be prevented from voting.[67] Ward, writing about the Colchester case in the Voice of the Fugitive newspaper, declared that the right to vote was the “most sacred” of all rights, and that even if white men took away everything from the black farmers in Colchester county, that would still be a lesser crime compared with losing the “right of a British vote”.[68] In 1859, Abraham Shadd become the first black elected to any office in what became Canada when he was elected to the town council in Raleigh in Kent county in Canada West.[69] In 1851, James Douglas became the governor of Vancouver Island, but that was not an elective one. Unlike in the United States, in Canada after the abolition of slavery in 1834, black Canadians were never stripped of their right to vote and hold office.[70]

Through often ignored, from time to time, black Canadians did receive notice. In 1857, William Hall of Horton, Nova Scotia, serving as a sailor in the Royal Navy, became the first black man to win the Victoria Cross, the highest decoration for valor in the British empire, for his actions at the siege of Lucknow.[71] Following the end of the American Civil War and subsequent emancipation of enslaved African Americans, a significant population remained, concentrated both within settlements established in the decades preceding the Civil War, and existing urban environments like Toronto.[72][73][74]

The Anti-Slavery Society of Canada estimated in its first report in 1852 that the "coloured population of Upper Canada" was about 30,000, of whom almost all adults were "fugitive slaves" from the United States.[75] St. Catharines, Ontario had a population of 6,000 at that time; 800 of its residents were "of African descent".[76] Many slaves sought refuge in Toronto which was known as a tolerant city. Black Canadians integrated in many areas of society, but the influence of slavery in the south still impacted these citizens. James Mink, an African Canadian who married his daughter to a white man, had his daughter sold into slavery during their honeymoon in the Southern States. She was freed after a large sum of money was paid and this behaviour was characterized as "a villainy that we are pleased to say characterizes few white [Toronto] men".[77]

West Coast[]

In 1858, James Douglas, the governor of the British colony of Vancouver Island, replied to an inquiry from a group of black people in San Francisco about the possibilities of settling in his jurisdiction. They were angered that the California legislature had passed discriminatory laws to restrict black people in the state, preventing them from owning property and requiring them to wear badges. Governor Douglas, whose mother was a "free coloured" person of mixed black and white ancestry from the Caribbean,[78] replied favourably. Later that year, an estimated 600 to 800 black Americans migrated to Victoria, settling on Vancouver Island and Salt Spring Island. At least two became successful merchants there: Peter Lester and Mifflin Wistar Gibbs. The latter also entered politics, being elected to the newly established City Council in the 1860s.

Gibbs returned to the United States with his family in the late 1860s after slavery had been abolished following the war; he settled in Little Rock, Arkansas, the capital of the state. He became an attorney and was elected as the first black judge in the US. He became a wealthy businessman who was involved with the Republican Party; in 1897 he was appointed by the President of the US as consul to Madagascar.

Immigration restrictions[]

In the early twentieth century, the Canadian government had an unofficial policy of restricting immigration by black people. The huge influx of immigrants from Europe and the United States in the period before World War I included few black people, as most immigrants were coming from Eastern and Southern Europe.

Clifford Sifton's 1910 immigration campaign had not anticipated that black Oklahomans and other black farmers from the Southern United States would apply to homestead in Amber Valley, Alberta and other parts of Canada.

However, Canada acted to restrict immigration by black persons, a policy that was formalised in 1911 by Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier:

"His excellency in Council, in virtue of the provisions of Sub-section (c) of Section 38 of the Immigration Act, is pleased to Order and it is hereby Ordered as follows: For a period of one year from and after the date hereof the landing in Canada shall be and the same is prohibited of any immigrants belonging to the Negro race, which race is deemed unsuitable to the climate and requirements of Canada."[31]

(Compare with the White Australia policy.)

Early 20th century[]

William Peyton Hubbard was the first visible minority and the first black citizen to be elected to public office at any level of government in a Canadian city.

The flow between the United States and Canada continued in the twentieth century. Some Black Canadians trace their ancestry to people who fled racism in Oklahoma, Texas, and other southern states in the early 1900s as part of the Great Migration out of the rural South, building new homesteads and communities – often block settlements – in Alberta and Saskatchewan just after they became provinces in 1905.[79] Examples include Amber Valley, Campsie, Junkins (now Wildwood) and Keystone (now Breton) in Alberta, as well as a former community in the Rural Municipality of Eldon, north of Maidstone, Saskatchewan (see, for example, Saskatchewan Municipal Heritage Property No. 439: the original log-style Shiloh (Charlow) Baptist Church and associated cemetery, 30 km north of Maidstone.)[80][81][82] Many of them were disappointed to encounter racism when they arrived in Canada, which they had regarded as a kind of Promised Land.[83]

Historically, black Canadians, being descended from either black Loyalists or American run-away slaves, had supported the Conservative Party as the party most inclined to maintain ties with Britain, which was seen as the nation that had given them freedom.[84] The Liberals were historically the party of continentalism (i.e moving Canada closer to the United States), which was not an appealing position for most black Canadians. In the first half of the 20th century, black Canadians usually voted solidly for the Conservatives as the party seen as the most pro-British.[85] Until the 1930s-1940s, the majority of black Canadians lived in rural areas, mostly in Ontario and Nova Scotia, which provided a certain degree of insulation from the effects of racism.[86] The self-contained nature of the rural black communities in Ontario and Nova Scotia with black farmers clustered together in certain rural counties meant that racism was not experienced on a daily basis.[87]The center of social life in the rural black communities were the churches, usually Methodist or Baptist, and ministers were generally the most important community leaders.[88] Through anti-black racism did exist in Canada, as the black population in Canada was extremely small, there was nothing comparable to the massive campaign directed against Asian immigration, the so-called "Yellow Peril", which was a major political issue in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, especially in British Columbia.[89]

The Conquerors depicting the 16th Canadian Scottish Battalion from Toronto in 1918 by Eric Kennington. Note the black man in the center, carrying the battalion's flag and another black man on the right in white blankets.

During the First World War, black volunteers to the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) were accepted, but officially were only assigned to construction units to dig trenches on the Western Front.[90] The Reverend William White, who commanded the all-black Number 2 Construction Company of the CEF, founded on 5 July 1916, become one of the few black men to receive an officer's commission in the CEF.[91] However, the Canadian historian René Chartrand noted that in the 1918 painting The Conquerors by Eric Kennington showing the men of the 16th Canadian Scottish battalion marching through a ruined landscape in France, one of the soldiers wearing kilts is a black man, which he used to suggest that sometimes black volunteers were assigned as front-line infantrymen.[92] Despite the rules restricting black Canadians to construction companies, about 2, 000 Canadians blacks fought as infantrymen in the CEF and several such as James Grant, Jeremiah Jones, Seymour Tyler, Roy Fells, and Curly Christian being noted for heroism under fire.[93] Jeremiah "Jerry" Jones of Truro, Nova Scotia enlisted in the 106th Battalion of the CEF in 1916 by lying about his age and was recommended for the Distinguished Conduct Medal for his heroism at Vimy Ridge, where he captured a German machine gun post and was wounded in action, but he never received it.[94] Later in 1917, Jones was badly wounded in the Battle of Passchendaele and was invalided out of the CEF in early 1918.[95] In 2010, Jones was posthumously awarded the Canadian Forces Distinguished Service Medal for his actions at Vimy Ridge.[96] James Grant, a black man from St. Catherine's, won the Military Cross in 1918, for taking a German artillery gun while under heavy fire.[97]

Jeremiah Jones of Truro, Nova Scotia was recommend for the Distinguished Conduct Medal for capturing a German machine post at Vimy Ridge in 1917.

A wave of immigration occurred in the 1920s, with black people from the Caribbean coming to work in the steel mills of Cape Breton, replacing those who had come from Alabama in 1899.[98] Many of Canada's railway porters were recruited from the U.S., with many coming from the South, New York City, and Washington, D.C. They settled mainly in the major cities of Montreal, Toronto, Winnipeg and Vancouver, which had major rail connections. The railroads were considered to have good positions, with steady work and a chance to travel.[99] A noted cause célèbre in the 1920s was the case of Matthew Bullock. He fled to Canada to avoid a potential lynching in North Carolina and fought extradition to the US.[100]

Starting in April 1920 with a series of articles by the left-wing British journalist E.D. Morel detailing alleged sexual crimes committed by the Senegalese serving in the French Army in the Rhineland, various left-wing groups in Britain, the United States and Canada started publicizing the so-called "Black Horror on the Rhine".[101] Morel's campaign was carried into Canada with the feminist Rose Henderson for instance warning in a 1925 article in The BC Federalist about the possibility of blacks being raised “to subdue and enslave the white peoples"[102] The willingness of various left-wing groups in Canada to promote the "Black Horror on the Rhine" campaign as part of the critique of the Treaty of Versailles as too harsh on Germany-which appealed to the worse racial fears by promoting the image of the Senegalese as brutes with superhuman strength and an insatiable need to rape white women-estranged black Canadians from the left in Canada during the interwar period. Another source of estrangement was the work of one of Canada's leading progressives, the feminist Emily Murphy. In a series of articles for Maclean's in the early 1920s, which were later turned into the 1922 book The Black Candle, Murphy blamed all of the problems on drug addiction amongst white Canadians on “Negro drug dealers" and Chinese opium dealers “of fishy blood”, accusing black Canadians and Chinese Canadians of trying to destroy white supremacy by getting white Canadians addicted to drugs.[103] The Black Candle was written in a sensationalist and lurid style meant to appeal to the racial fears of white Canadians, and in this Murphy was completely successful.[104] Due to the popularity of The Black Candle, Chinese immigration to Canada was stopped via the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1923. Marijuana was also banned in 1923 out of the fear prompted by Murphy that marijuana was a drug used by black Canadians to "corrupt" white Canadians.[105] A report by the Senate in 2002 noted: “Early drug legislation was largely based on a moral panic, racist sentiment and a notorious absence of debate.”[106] Perhaps even more importantly, Murphy established a perceived connection between black Canadians, drugs, and crime in the minds of white Canadians that continues to this day.

Montreal was the largest and most wealthiest city in Canada in the 1920s and also the most cosmopolitan, having a French-Canadian majority with substantial English, Scots, Irish, Italian, and Jewish communities. The multi-cultural atmosphere in Montreal allowed a black community to be established in the 1920s. The black community that emerged in Montreal in the 1920s was largely American in origin, centering around the "sporting district" between St. Antoine and Bonaventure streets, which had a reputation as a "cool" neighborhood, known for its lively and often riotous nightclubs that opened at 11:00 pm and closed at 5:00 am, where the latest in Afro-American jazz was played, alcohol was consumed in conspicuous quantities, and illegal gambling was usually tolerated.[107] The Nemderloc Club (nemderloc being "colored men" spelled backwards), which opened in 1922, was the most famous black club in Montreal, being very popular with both locals and Americans seeking to escape Prohibition by coming to Canada, where alcohol was still legal, hence the saying that American tourists wanted to "drink Canada dry".[108] Many of the Afro-Americans who settled in the "sporting district" of Montreal came from Harlem to seek a place where it was legal to drink alcohol.[109] Relations between the police and the black community in Montreal were unfriendly with the St. Antoine district being regularly raided by the police looking for illegal drugs and gambling establishments.[110] Despite its reputation as the "coolest" neighborhood in Montreal, the St. Antoine neighborhood was a center of poverty with the water being unsafe to drink and a death rate that was twice the norm in Montreal.[111]

As the Afro-Americans who came to work as railroad porters in Canada were all men, about 40% of the black men living in Montreal in the 1920s were married to white women.[112] This statistic excluded those in common-law relationships, which were also common, and which estranged the black community of Montreal from the conservative and deeply Christian rural black communities in Ontario and Nova Scotia, who were offended by the prevalence of casual sex and common-law relationships in the black community in Montreal.[113] The Afro-American community in Montreal was seen, perhaps not entirely fairly, as a center of debauchery and licentiousness by the other black communities in Canada, who made a point of insisting that Montreal was not all representative of their communities.[114] The West Indian communities in the Maritime provinces, with the largest number working in the Cape Breton steel mills and in the Halifax shipyards always referred pejoratively to the older black community in Nova Scotia as the "Canadians" and the black communities in Quebec and Ontario as the "Americans".[115] The West Indian communities in Nova Scotia in the 1920s were Anglican, fond of playing cricket, and unlike the other black communities in Canada were often involved in Back-to-Africa movements.[116]

The historian Robin Winks described the various black Canadian communitites in the 1920s as being very diverse, which he described as being made up of "...rural blacks from small towns in Nova Scotia, prosperous farmers from Ontario, long-time residents of Vancouver Island, sophisticated New York newcomers to Montreal, activist West Indians who were not, they insisted, Negroes at all"-indeed so diverse that unity was difficult.[117] At the same time, Winks wrote that racism in Canada lacked a "consistent pattern" as "racial borders shifted, gave way, and stood firm without consistency, predictability or even credibility".[118] Inspired by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in the United States, in 1924 J.W. Montgomery of Toronto and James Jenkins of London founded the Canadian League for the Advancement of Colored People as an umbrella group for all of the Canadian black communities.[119] Another attempt to provide unity for the black communities in Canada was made by the followers of Marcus Garvey's United Negro Improvement Association, which opened its first Canadian branch in Montreal in 1919.[120] After his deportation from the United States in 1927, Garvey settled in Montreal in 1928.[121] However, when Garvey urged his American followers not to vote for Herbert Hoover in the 1928 election, the American consul in Montreal complained about this "interference" in American politics and Garvey was expelled from Canada at the urging of the U.S. government.[122] Garvey was allowed to return to Canada in 1936 and 1937 where he held rallies in Toronto preaching his Back-to-Africa message.[123] Garvey, an extremely charismatic man who inspired intense devotion in his followers, proved to be a divisive and controversial figure with his Back-to-Africa message and his insistence that black people embrace segregation as the best way forward.[124] Most black Canadian community leaders rejected Garvey's message, arguing that Canada, not Africa, was their home and that embracing segregation was a retrogressive and self-defeating move.[125]

The Great Depression hit rural Canada very hard and black Canadian farmers especially hard.[126] One consequence was that many of the black Canadian villages and hamlets in Ontario and Nova Scotia, some which were founded in the 18th century as Loyalist settlements, became abandoned as their inhabitants moved to the cities in search of work.[127] In turn, the movement of black Canadians to the cities brought them brutally face to face with racism as a series of informal "Jim Crow" restrictions governed restaurants, bars, hotels, and theaters while many landlords refused to rent to black tenants.[128] In October 1937, when a black man purchased a house in Trenton, Nova Scotia, hundreds of white people stormed the house, beat up its owner and destroyed the house under the grounds that a black man moving into the neighborhood would depress property values.[129] Inspired by the unwillingness of the police to protect a black man, the mob then destroyed two other homes owned by black men, an action praised by the mayor for raising property values in Trenton, and the only person charged by the police was a black man who punched out a white trying to destroy his home.[130] Many black Nova Scotians moved into a neighborhood of Halifax that came to be known as Africville, which the white population of Halifax called "Nigger Town".[131] Segregation in Truro, Nova Scotia was practiced so fiercely that its black residents took to calling it "Little Mississippi".[132] The 1930s saw a dramatic increase in the number and activities of black self-help groups to deal with the impact of racism and the Depression.[133] Another change wrought by the Depression was a change in black families as most married black women had to work in order to provide for their families, marking the end of an era when only the husband worked.[134]

In the Second World War, black volunteers to the armed forces were initially refused, but the Canadian Army starting in 1940 agreed to take black volunteers, and by 1942 were willing to give blacks officers' commissions.[135] Unlike in World War I, there were no segregated units in the Army and Canadian blacks always served in integrated units.[136] The Army was rather more open to black Canadians rather than the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) and the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF), which both refused for some time to accept black volunteers.[137] By 1942, the RCN had accepted Canadian blacks as sailors while the RCAF had accepted blacks as ground crews and even as airmen, which meant giving them an officer's commission as in the RCAF airmen were always officers.[138] In 1942, newspapers gave national coverage when the five Carty brothers of Saint John, New Brunswick all enlisted in the RCAF on the same day with the general subtext being that Canada was more tolerant than the United States in allowing the black Carty brothers to serve in the RCAF.[139] The youngest of the Carty brothers, Gerald Carty, served as a tail gunner on a Halifax bomber, flying 35 missions to bomb Germany and was wounded in action.[140] The mobilization of the Canadian economy for "total war" gave increased economic opportunities for both black men and even more so for black women, many of whom for the first time in their lives found well-paying jobs in war industries.[141]

In general racism became less fashionable during World War II with two incidents in 1940 illustrating a tendency towards increased tolerance as feelings of wartime national solidarity made display of prejudice less acceptable.[142] A Vancouver bar that refused to serve a black man was fined by a judge when the said man complained while in Toronto a skating rink that turned away blacks found itself the object of a boycott and demonstrations by students from the University of Toronto until the owners of the rink finally agreed to accept black patrons.[143] The incidents in Toronto and Vancouver, as small as they were, would have been inconceivable ten or even five years before.[144] Winks wrote that if the Second World War was not the end of racism in Canada, but it was the beginning of the end as for the first time that many practices that been considered normal were subject to increasing vocal criticism as many black Canadians started to become more assertive.[145]

In 1942, following complaints from black university graduates that the National Selective Service board assigned them inferior work, a campaign waged by the Globe & Mail newspaper, the Canadian Jewish Congress, and the Winnipeg Free Press won a promise from the National Selective Service board to stop using race when assigning potential employees to employers.[146] During the war, unions became more open to accepting black members and Winks wrote the "most important change" to black Canadian community caused by World War II was "the new militancy in the organized black labor unions".[147] The most militant black unions was the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, which during the war won major wage increases for black porters working on the railroads.[148] In Winnipeg, a Joint Labor Committee to Combat Racial Intolerance was formed to end discrimination against Jews and Ukrainian-Canadians, but soon agreed to take cases concerning black Canadians.[149] In 1944, Ontario passed the Racial Discrimination Act, which banned the use of any symbol or sign by any businesses with the aim of racial discrimination, which was the first law in Canada intended to address the practice of many businesses of refusing to take black customers.[150]

In 1946, a black woman from Halifax, Viola Desmond, watched a film in a segregated cinema in New Glasgow, Nova Scotia, which to her being dragged out of the theater by the manager and a policeman and to her being fined for not paying the one cent difference in sales tax between buying a ticket in the white section, where she sat, and the black section, where she was supposed to sat.[151] The Desmond case attracted much publicity as various civil rights groups rallied in her defense. Desmond fought the fine in the appeals court, where she lost, but the incident led the Nova Scotia Association for the Advancement of Colored People to pressure the Nova Scotia government to pass the Fair Employment Act of 1955 and Fair Accommodations Act of 1959.[152] Following more pressure from black Canadian groups, in 1951 Ontario the Fair Employment Practices Act outlawing racial discrimination in employment and the Fair Accommodation Practices Act of 1955.[153] In 1958, Ontario established the Anti-Discrimination Commission, which was renamed the Human Rights Commission in 1961.[154] Led by the American-born black sociologist Daniel G. Hill, the Ontario Anti-Discrimination Commission investigated 2, 000 cases of racial discrimination in first two years, and was described as having a beneficial effect on the ability of Canadian blacks to obtain employment.[155] In 1953, Manitoba passed the Fair Employment Act, which was modeled after the Ontario law, and New Brunswick, Saskatchewan and British Columbia passed similar laws in 1956, followed by Quebec in 1964.[156] In March 1960, in the Sharpeville massacre, the South African police gunned 67 black South Africans protesting apartheid, which in sign of changing racial attitudes, caused much controversy in Canada.[157] There was considerable public pressure on the Prime Minister John Diefenbaker to ask for South Africa to be expelled from the Commonwealth following the Sharpeville massacre with many noting that the South African prime minister Hendrik Verwoerd was an admirer of Nazi Germany.[158] At the conference of Commonwealth prime ministers in London in 1960, Diefenbaker tried to avoid discussing the subject of expelling South Africa, but at the next conference in London in 1961, he played a leading role in passing a resolution declaring racial discrimination incompatible with Commonwealth membership, which led to Verwoerd storming of the conference and quitting the Commonwealth.[159] The subject of condemning South Africa for apartheid benefited the black Canadians since it suggested that racism was not longer acceptable..[160]

Late 20th century and early 21st century[]

Canada maintained its restrictions of immigration until 1962, when racial rules were eliminated from the immigration laws. This coincided with the dissolution of the British Empire in the Caribbean. By the mid-1960s, approximately 15,000 Caribbean immigrants had settled in Toronto.[161] Over the next decades, several hundred thousand Afro-Caribbeans arrived, becoming the predominant black population in Canada. Between 1950 and 1995, about 300,000 people from the West Indies settled in Canada.[162] Outside of the Maritime provinces, where the majority of the black population are the descendants of black Loyalists and American runaway slaves, the majority of black Canadians are descended from immigrants from the West Indies.[163] Since then, an increasing number of new immigrants from Africa have been coming to Canada;[14] they have also immigrated to the United States and Europe. This includes large numbers of refugees, but also many skilled and professional workers pursuing better economic conditions. About 150,000 people from Africa immigrated to Canada between 1950 and 1995.[164] Today's Black Canadians are largely of Caribbean origin, with some of recent African origin, and smaller numbers from the United States, Europe and Latin America.

However, a sizable number of Black Canadians who descend from freed American slaves can still be found in Nova Scotia and parts of Southwestern Ontario. Some descendants of the freed American slaves, many of whom were of mixed race descent, have mixed into the white Canadian community and have mostly lost their ethnic identity. Some descendants returned to the United States. Bangor, Maine, for example, received many Black Canadians from the Maritime provinces.[165]

Like other recent immigrants to Canada, Black Canadian immigrants have settled preferentially in provinces matching the language of their country of origin. Thus, in 2001, 90% of Canadians of Haitian origin lived in Quebec,[166] while 85% of Canadians of Jamaican origin lived in Ontario.[167] A major change in the settlement patterns of black Canadians occurred in the second half of the 20th century as the mostly rural black Canadian communities had become mostly urban communities, a process starting in the 1930s that was complete by the 1970s.[168] Immigrants from the West Indies almost always settled in the cities, and the Canadian historian James Walker called the black Canadian community one of the "most urbanized of all Canada's ethnic groups".[169]

On 29 January 1969, at Sir George Williams University in Montreal, the Sir George Williams affair began with a group of about 200 students, many of whom were black, occupied the Henry Hall computer building in protest against allegations that a white biology professor, Perry Anderson, was biased in grading black students, which the university had dismissed.[170] The student occupation ended in violence on 11 February 1969 when the riot squad of the Service de police de la Ville de Montréal stormed the Hall building, a fire was started causing $2 million worth of damage (it is disputed whatever the police or the students started the fire), and many of the protesting students were beaten and arrested.[171] The entire event received much media attention; it was recorded live for television by the news crews present. As the Hall building burned and the policemen beat the students, onlookers in the crowds outside chanted "Burn, niggers, burn!" and "Let the niggers burn!".[172] Afterwards, the protesting students were divided by race by the police with charges laid against the 97 black students present in the Hall building. The two leaders of the protest, Roosevelt “Rosie” Douglas and Anne Cools, were convicted and imprisoned with Douglas being deported back to Dominica after completing his sentence, where he later became Prime Minister.[173] Cools received a royal pardon and was appointed to the Senate in 1984 by Pierre Trudeau, becoming the first black senator. The riot at Sir George Williams University spurred-through it did not start-a wave of "black power" activism in Canada with many blacks taking the view that the police response was disproportionate and unjustifiably violent while many white Canadians who had believed that their country had no racism were shocked by a race riot in Canada.[174]

In July 1967, the Caribana festival was started in Toronto by immigrants from the West Indies to celebrate West Indian culture that has become one of the largest celebrations of Caribbean culture in North America. In 1975, a museum telling the stories of African Canadians and their journeys and contributions was established in Amherstburg, Ontario, entitled the Amherstburg Freedom Museum.[175] In Atlantic Canada, the Black Cultural Centre for Nova Scotia was established in Cherrybrook.

Starting in the 1960s with the weakening of ties to Britain together the changes caused by immigration from the West Indies, black Canadians have become active in the Liberal and New Democratic parties as well as the Conservatives.[176] In 1963, the Liberal Leonard Braithwaite became the first black person elected to a provincial legislature when he was elected as a MPP in Ontario.[177] In the 1968 election, Lincoln Alexander was elected as a Progressive Conservative for the riding of Hamilton West, becoming the first black person elected to the House of Commons.[178] In 1979, Alexander become the first black federal Cabinet minister when he was appointed minister of labor in the government of Joe Clark. In 1972, Emery Barnes and Rosemary Brown were elected to the British Columbia legislation as New Democrats.[179] In 1984, the New Democrat Howard McCurdy was elected to the House of Commons as the second black MP while Anne Cools became the first black Senator.[180] In 1985, the Liberal Alvin Curling became the second black man elected to the Ontario legislation, and the first black person to serve as a member of the Ontario cabinet.[181] In 1990, the New Democrat Zanana Akande became the first black female MPP in Ontario and the first black woman to join a provincial cabinet as the minister of community services in the government of Bob Rae.[182] In 1990, the Conservative Donald Oliver became the first black man appointed to the Senate.[183] In 1993, Liberal Wayne Adams became the first black person elected to the Nova Scotia legislation and the first black Nova Scotia cabinet minister.[184] In the 1993 election, Jean Augustine and Hedy Fry were elected to the House of Commons as Liberals, becoming the first female black MPs.[185] In 1996, Fry was promoted up from the backbenches to become the minister for multiculturalism and status of women, making her the first black female federal cabinet minister.[186]

A recurring point of tension in the Toronto region since the 1980s has concerned allegations of police harassment and violence against the black population in the Toronto area. After the killing of Lester Donaldson by the Toronto police in August 1988, the Black Action Defence Committee (BADC) was founded in October 1988 to protest allegations of police brutality against black Canadians in Toronto. The founder of BADC, the Jamaican immigrant Dudley Laws became one of the most recognized figures in Toronto in the 1990s, noted for his willingness to confront the police.[187] Alvin Curling told the Toronto Star in 2013: “I think BADC raised the question that this wonderful looking society of Canada and Toronto, as organized as it was, had some systemic racism going on and police behaviour that was not acceptable.”[188] In April 1992, two white Peel Region police officers were acquitted for killing a 17-year black man, Michael Wade Lawson, who was riding in a stolen car, and then on 2 May 1992, a Toronto police officer killed a 22-year-old black man, Raymond Lawrence, claiming he was wielding a knife, through Lawrence's fingerprints were not found on the knife that was found on his corpse.[189]

On the evening of 4 May 1992, a march was held on Toronto's Yonge Street by the BADC to protest the killings of Lawrence and Lawson together the acquittal of the police officers who had beaten Rodney King in Los Angeles that was joined by thousands of people who marched to the U.S consulate in Toronto.[190] After holding a sit-in in front of the American consulate, at about 9 pm, the protest turned violent as some of the protesters began to break windows and loot stores on Yonge Street, shouting "“No Justice No Peace!".[191] Recently, what was widely described at the time as a race riot in Toronto had been relabeled by Brock university professor Simon Black as an "uprising" reflecting long-standing racial tensions in Toronto.[192] However, other observers of the 1992 riot have described the majority of the looting and vandalism as done by white youths, leading to questions whatever it is appropriate to describe the 1992 riot as a "race riot".[193] The issue of police harassment of blacks in Toronto has continued into the 21st century. In 2015, the Toronto journalist Desmond Cole published an article in Toronto Life entitled “The Skin I’m In: I’ve been interrogated by police more than 50 times—all because I’m black”, accusing the police of harassing him for his skin color.[194]

With the secularization of society in late 20th century, the churches have ceased to play the traditionally dominant role in black Canadian communities.[195] Increased educational and job opportunities have led to many black women to seek full-time careers.[196] According to the census of 1991, black Canadians on average received lower wages than white Canadians.[197] However, immigrants from the West Indies and Africa have usually arrived with high level of skills and education, finding work in numerous occupational categories.[198] Efforts have been made to address the long-standing educational gap between black and white Canadians, and in the recent decades, black Canadians have been making economic gains.[199]

Statistics[]

- About 30% of Black Canadians have Jamaican heritage.[200]

- An additional 32% have heritage elsewhere in the Caribbean or Bermuda.[14]

- 60% of Black Canadians are under the age of 35.[14]

- 57% of Black Canadians live in the province of Ontario.[201]

- 97% of Black Canadians live in urban areas.[14]

- Black women in Canada outnumber black men by 32,000.[9]

Below is a list of provinces, with the number of Black Canadians in each province and their percentage of population.[202]

| Province | 2001 Census | % 2001 | 2011 Census | % 2011 | 2016 Census | % 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 411,090 | 3.6% | 539,205 | 4.3% | 627,715 | 4.7% | |

| 152,195 | 2.1% | 243,625 | 3.2% | 319,230 | 4.0% | |

| 31,395 | 1.1% | 74,435 | 2.1% | 129,390 | 3.3% | |

| 25,465 | 0.7% | 33,260 | 0.8% | 43,500 | 1.0% | |

| 12,820 | 1.2% | 19,610 | 1.7% | 30,335 | 2.4% | |

| 19,230 | 2.1% | 20,790 | 2.3% | 21,915 | 2.4% | |

| 4,165 | 0.4% | 7,255 | 0.7% | 14,925 | 1.4% | |

| 3,850 | 0.5% | 4,870 | 0.7% | 7,000 | 1.0% | |

| 840 | 0.2% | 1,455 | 0.3% | 2,355 | 0.5% | |

| 370 | 0.3% | 390 | 0.3% | 825 | 0.6% | |

| 175 | 0.5% | 555 | 1.4% | 760 | 1.8% | |

| 65 | 0.3% | 120 | 0.4% | 330 | 0.9% | |

| 120 | 0.4% | 100 | 0.3% | 270 | 0.8% | |

| 662,215 | 2.2% | 945,665 | 2.9% | 1,198,540 | 3.5% |

List of census subdivisions with Black populations higher than the national average[]

Source: Canada 2016 Census[13]

National average: 3.5% (1,198,540)

Alberta[]

Manitoba[]

- Winnipeg (3.9%)

New Brunswick[]

- Hampstead Parish (6.3%)

- Cap-Pelé (3.6%)

Nova Scotia[]

- Shelburne (town) (7.5%)

- Lake Echo (6.1%)

- New Glasgow (5.4%)

- Yarmouth (town) (4.6%)

- Guysborough (4.4%)

- Truro (4.2%)

- Digby (municipal district) (4.1%)

- Halifax (3.8%)

- Windsor (3.6%)

- Antigonish (3.5%)

Ontario[]

- Ajax (16.7%)

- Brampton (13.9%)

- Pickering (10.8%)

- Shelburne (9.5%)

- Toronto (8.9%)

- Whitby (8%)

- Ottawa (6.6%)

- Mississauga (6.6%)

- Oshawa (5.5%)

- Dresden (5.4%)

- Windsor (5%)

- Milton (4.8%)

- Kitchener (4.1%)

- Hamilton (3.8%)

Quebec[]

- Montréal (10.3%)

- Châteauguay (8.3%)

- Laval (7.8%)

- Terrebonne (7.2%)

- Repentigny (7.1%)

- Longueuil (7%)

- Dollard-des-Ormeaux (6.8%)

- Gatineau (6.1%)

- Pincourt (5.6%)

- Brossard (5.2%)

- Vaudreuil-Dorion (4.7%)

- Côte Saint-Luc (4.3%)

- Dorval (4.3%)

Settlements[]

Although many Black Canadians live in integrated communities, a number of notable Black communities have been known, both as unique settlements and as Black-dominated neighbourhoods in urban centres.

The most historically documented Black settlement in Canadian history is the defunct community of Africville, a district located at the North End of peninsular Halifax, Nova Scotia. Its population was relocated and it was demolished in the 1960s to facilitate the urban expansion of the city. Similarly, the Hogan's Alley neighbourhood in Vancouver was largely demolished in 1970, with only a single small laneway in Strathcona remaining.

The Wilberforce Colony in Ontario was also a historically Black settlement. It evolved demographically as Black settlers moved away. It became dominated by ethnic Irish settlers, who renamed the village Lucan. A small group of Black American settlers from San Francisco were the original inhabitants of Saltspring Island in the mid-19th century.

Other notable Black settlements include North Preston in Nova Scotia, Priceville, Shanty Bay, South Buxton and Dresden in Ontario, the Maidstone/Eldon area in Saskatchewan[203] and Amber Valley in Alberta. North Preston currently has the highest concentration of Black Canadians in Canada, many of whom are descendants of Africville residents. Elm Hill in Hampstead Parish is the last remaining black community in New Brunswick.[204]

One of the most famous Black-dominated urban neighbourhoods in Canada is Montreal's Little Burgundy, regarded as the spiritual home of Canadian jazz due to its association with many of Canada's most influential early jazz musicians. In present-day Montreal, Little Burgundy and the boroughs of Côte-des-Neiges–Notre-Dame-de-Grâce, LaSalle, Pierrefonds-Roxboro, Villeray–Saint-Michel–Parc-Extension, and Montréal-Nord have large Black populations, the latter of which has a large Haitian population. Several cities in Greater Montreal such as Laval, Terrebonne, Repentigny and Châteauguay also have large Black populations.

In Winnipeg, the Central Park neighborhood has the largest concentration of Black Canadians in Manitoba. Nearly 25% of area residents are black, as of 2016.[205] The Queen Mary Park and Central McDougall neighbourhoods form the center of the black community in Edmonton. Queen Mary Park has been home to a long-standing African American population since the early 1900s, centered around Shiloh Baptist Church, although today the neighbourhood is composed mostly of recent migrants from Africa.[206][207][208]

In Toronto, many Blacks settled in St. John's Ward, a district which was located in the city's core.[209][210] Others preferred to live in York Township, on the outskirts of the city. By 1850, there were more than a dozen Black businesses along King Street;[209] the modern-day equivalent is Little Jamaica along Eglinton Avenue, which contains one of the largest concentrations of Black businesses in Canada.[211]

Several urban neighbourhoods in Toronto, including Jane and Finch, Rexdale, Downsview, Malvern, Weston, St. James Town, and Lawrence Heights have large Black Canadian communities.[212] The Toronto suburbs of Brampton and Ajax also have sizable Black populations, many of whom are middle income professionals and small business owners.[213][214] The Greater Toronto Area is home to a highly educated middle to upper middle class Black population who continue to migrate out of the city limits, into surrounding suburbs.

Culture[]

Media representation of Blacks in Canada has increased significantly in recent years, with television series such as Drop the Beat, Lord Have Mercy!, Diggstown and Da Kink in My Hair focusing principally on Black characters and communities.

The films of Clement Virgo, Sudz Sutherland and Charles Officer have been among the most prominent depictions of Black Canadians on the big screen. Notable films have included Sutherland's Love, Sex and Eating the Bones, Officer's Nurse.Fighter.Boy and Virgo's Rude and Love Come Down.

In literature, the most prominent and famous Black Canadian writers have been Josiah Henson, George Elliott Clarke, Lawrence Hill, Dionne Brand and Dany Laferrière, although numerous emerging writers have gained attention in the 1990s and 2000s.

Since the late 19th century, Black Canadians have made significant contributions to the culture of sports, starting with the founding of the Coloured Hockey League in Nova Scotia.[215] In North America's four major professional sports leagues, several Black Canadians have had successful careers, including Ferguson Jenkins (Baseball Hall of Fame member), Grant Fuhr (Hockey Hall of Fame member), Jarome Iginla, Russell Martin, and Jamaal Magloire; most recently, Andrew Wiggins and P. K. Subban have achieved a high level of success. In athletics, Harry Jerome, Ben Johnson, and Donovan Bailey were Canada's most prominent Black sprinters in recent decades; the current generation is led by Andre De Grasse.

The largest and most famous Black Canadian cultural event is the Scotiabank Toronto Caribbean Carnival (also known as Caribana), an annual festival of Caribbean Canadian culture in Toronto which typically attracts at least a million participants each year.[216] The festival incorporates the diversities that exist among the Canadians of African and Caribbean descent.

Black Canadians have had a major influence on Canadian music, helping pioneer many genres including Canadian hip hop, Canadian blues, Canadian jazz, R&B, Caribbean music, pop music and classical music.[217] Some of the earliest musical influences include Robert Nathaniel Dett, Portia White, Oscar Peterson and Charlie Biddle. Some Black Canadian musicians have enjoyed mainstream worldwide appeal in various genres, such as Dan Hill, Glenn Lewis, Tamia, Deborah Cox, and Kardinal Offishall.

While African American culture is a significant influence on its Canadian counterpart, many African and Caribbean Canadians reject the suggestion that their own culture is not distinctive.[4] In his first major hit single "BaKardi Slang", rapper Kardinal Offishall performed a lyric about Toronto's distinctive Black Canadian slang:

| “ | We don't say 'you know what I'm sayin', T dot says 'ya dun know' We don't say 'hey that's the breaks', we say 'yo, a so it go' We don't say 'you get one chance', We say 'you better rip the show'... Y'all talking about 'cuttin and hittin skins', We talkin bout 'beat dat face'... You cats is steady saying 'word', My cats is steady yellin 'zeen'... So when we singin about the girls we singin about the 'gyal dem' Y'all talkin about 'say that one more time', We talkin about 'yo, come again' Y'all talkin about 'that nigga's a punk', We talkin about 'that yout's a fosse'... A shoe is called a 'crep', A big party is a 'fete' Ya'll takin about 'watch where you goin!', We talkin about 'mind where you step!' |

” |

Because the visibility of distinctively Black Canadian cultural output is still a relatively recent phenomenon, academic, critical and sociological analysis of Black Canadian literature, music, television and film tends to focus on the ways in which cultural creators are actively engaging the process of creating a cultural space for themselves which is distinct from both mainstream Canadian culture and African American culture.[4] For example, most of the Black-themed television series which have been produced in Canada to date have been ensemble cast comedy or drama series centred on the creation and/or expansion of a Black-oriented cultural or community institution.[4]

The Book of Negroes, a CBC Television miniseries about slavery based on Lawrence Hill's award-winning novel, was a significant ratings success in January 2015.[218]

Racism[]

In a 2013 survey of 80 countries by the World Values Survey, Canada ranked among the most racially tolerant societies in the world.[219] Nevertheless, according to Statistics Canada's "Ethnic Diversity Survey", released in September 2003, when asked about the five-year period from 1998 to 2002 nearly one-third (32%) of respondents who identified as black reported that they had been subjected to some form of racial discrimination or unfair treatment "sometimes" or "often".[220]

From the late 1970s to the early 1990s, many unarmed black Canadian men in Toronto were shot or killed by Toronto Police officers.[221][222] In response, the Black Action Defence Committee (BADC) was founded in 1988. BADC's executive director, Dudley Laws, claimed that Toronto had the "most murderous" police force in North America, and that police bias against blacks in Toronto was worse than in Los Angeles.[222][223] In 1990, BADC was primarily responsible for the creation of Ontario's Special Investigations Unit, which investigates police misconduct.[222][224] Since the early 1990s, the relationship between Toronto Police and the city's black community has improved;[222] in 2015, Mark Saunders became the first black police chief in the city's history. Carding remained an issue as of 2016;[225] restrictions against arbitrary carding came into effect in Ontario in 2017.[226]

Throughout the years, high-profile cases of racism against black Canadians have occurred in Nova Scotia.[227][228][229] The province in Atlantic Canada continues to champion human rights and battle against racism, in part by an annual march to end racism against people of African descent.[230][231]

Additionally, Black Canadians have historically faced incarceration rates disproportionate to their population. In 1911, black Canadians constituted 0.22% of the population of Canada but 0.321% in prison. White Canadians were incarcerated at a rate of 0.018%. By 1931, 0.385% of black Canadians were in prison, compared to 0.035 of white Canadians.[232]

Contemporary rates of incarceration of black Canadians have continued to be disproportionate to their percentage of the general population, with 1 in 10 federal prisoners being black but being 2.9% of the population.[233]

See also[]

- List of black Canadians

- African diaspora

- African-Canadian Heritage Tour

- List of topics related to the African diaspora

- Slavery in Canada

- Amherstburg Freedom Museum

- Black Cultural Centre for Nova Scotia

- Demographics of Canada

- Black Canadians in the Greater Toronto Area

- Black Canadians in Montreal

References[]

- Specific

- ^ Harrison, Faye Venetia (2005). Resisting racism and xenophobia : global perspectives on race, gender, and human rights. AltaMira Press. p. 180. ISBN 0-7591-0482-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=-mHGl5HnEBIC&lpg=PR3&ots=4QssZWqzcr&dq=Resisting%20racism%20and%20xenophobia%3A%20global%20perspectives%20on%20race&pg=PA180#v=onepage&q&f=true.

- ^ a b Magocsi, Paul Robert (1999). Encyclopedia of Canada's Peoples. University of Toronto Press, Scholarly Publishing Division. ISBN 0-8020-2938-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=dbUuX0mnvQMC&lpg=PP1&dq=Encyclopedia%20of%20Canada%27s%20Peoples&pg=PA139#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- ^ "2006 Census of Canada – Ethnic Origin". http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2006/dp-pd/tbt/Rp-eng.cfm?A=R&APATH=3&D1=0&D2=0&D3=0&D4=0&D5=0&D6=0&DETAIL=0&DIM=0&FL=A&FREE=0&GC=01&GID=837928&GK=1&GRP=1&LANG=E&O=D&PID=92333&PRID=0&PTYPE=88971%2C97154&S=0&SHOWALL=0&SUB=0&TABID=1&THEME=80&Temporal=2006&VID=0&VNAMEE=&VNAMEF=.

- ^ a b c d e f Rinaldo Walcott, Black Like Who?: Writing Black Canada. 2003, Insomniac Press. ISBN 1-894663-40-3.

- ^ a b "As for terminology, in Canada, it is still appropriate to say Black Canadians." Valerie Pruegger, "Black History Month". Culture and Community Spirit, Government of Alberta.

- ^ Rosemary Sadlier. "Black History Canada – Black Contributions". Blackhistorycanada.ca. http://blackhistorycanada.ca/theme.php?id=7. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- ^ "Black History Canada – Noteworthy Personalities". Blackhistorycanada.ca. http://blackhistorycanada.ca/topic.php?id=158&themeid=7. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- ^ a b c d "Visible minority groups, 2006 counts, for Canada, provinces and territories". 2.statcan.ca. 2010-10-06. http://www12.statcan.ca/english/census06/data/highlights/ethnic/pages/Page.cfm?Lang=E&Geo=PR&Code=01&Table=1&Data=Count&StartRec=1&Sort=11&Display=Page&CSDFilter=5000. Retrieved 2011-01-22.