| ||||||||||||||

| Arlington County, Virginia | ||

| ||

Location in the state of Virginia | ||

Virginia's location in the U.S. | ||

| Founded | February 27, 1801 | |

|---|---|---|

| Seat | Arlington | |

| Area - Total - Land - Water |

26 sq mi (67 km²) 26 sq mi (67 km²) 0 sq mi (0 km²), 0.35% | |

| Population - (2020) - Density |

238,643 7,995/sq mi (3,087/km²) | |

| Website | www.arlingtonva.us | |

Looking north toward The Pentagon with Rosslyn in the background.

Looking south toward Arlington's Rosslyn and Crystal City skylines from Georgetown University.

Arlington County is a county in the Commonwealth of Virginia. The land that became Arlington was originally donated by Virginia to the United States government to form part of the new federal capital district. On February 27, 1801, the United States Congress organized the area as a subdivision of the District of Columbia named Alexandria County. Due to issues involving Congressional representation, the abolition of slavery, and economic decline, Congress returned Alexandria to the Commonwealth of Virginia in 1846. The state legislature changed the county's name to Arlington in 1920 to avoid confusion with the adjacent City of Alexandria.

The county is situated in Northern Virginia on the south bank of the Potomac River directly across from Washington, D.C. Arlington is also bordered by Fairfax County and the City of Falls Church to the southwest, and the City of Alexandria to the southeast. With a land area of 26 square miles (67 km2), Arlington is the geographically smallest self-governing county in the United States and has no other incorporated towns within its borders. Given these unique characteristics, for statistical purposes the county is included as a municipality within the Washington Metropolitan Area by the United States Census Bureau. As of 2020, Arlington County had a population of 238,643 residents.

Given the county's proximity to Washington, D.C., Arlington is headquarters to many departments and agencies of the federal government of the United States, including the Pentagon, the Department of Defense, the United States Drug Enforcement Agency, and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). The many federal agencies, government contractors, and service industries contribute to Arlington's stable economy, which has made it one of the highest-income counties in the United States. Arlington is also the location of national memorials and museums, including Arlington National Cemetery, the Pentagon Memorial, the Marine Corps War Memorial, and the United States Air Force Memorial.

History[]

Foundation[]

The area that now forms Arlington County was originally part of Fairfax County in the Colony of Virginia. Land grants from the British monarch were awarded to prominent Englishmen in exchange for political favors and efforts at development. One of the grantees was Thomas Fairfax, 6th Lord Fairfax of Cameron whose lends his name to both Fairfax County and the City of Fairfax. The name Arlington comes from Henry Bennet, 1st Earl of Arlington whose name had been applied to a plantation along the Potomac River. George Washington Parke Custis, grandson of First Lady Martha Washington, acquired this land in 1802. The estate was eventually passed down to Mary Anna Custis Lee, wife of General Robert E. Lee.[1] The property later became Arlington National Cemetery during the American Civil War, and now lends its name to present-day Arlington County.

The area that now contains Arlington County was ceded to the new United States federal government by the Commonwealth of Virginia. With the passage of the Residence Act in 1790, Congress approved a new permanent capital to be located on the Potomac River, the exact area to be selected by President George Washington. The Residence Act originally only allowed the President to select a location within Maryland as far east as what is now the Anacostia River. However, President Washington shifted the federal territory's borders to the southeast in order to include the pre-existing city of Alexandria at the District's southern tip. In 1791, Congress amended the Residence Act to approve the new site, including the territory ceded by Virginia.[2] However, this amendment to the Residence Act specifically prohibited the "erection of the public buildings otherwise than on the Maryland side of the River Potomac."[3] As permitted by the U.S. Constitution, the initial shape of the federal district was a square, measuring 10 miles (16 km) on each side, totaling 100 square miles (260 km2). During 1791–92, Andrew Ellicott and several assistants placed boundary stones at every mile point. Fourteen of these markers were in Virginia and many of the stones are still standing.[4]

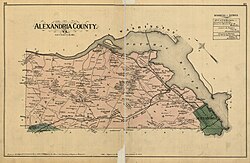

1878 map of Alexandria County, now Arlington County

When Congress arrived in the new capital, they passed the Organic Act of 1801 to officially organize the District of Columbia and placed the entire federal territory, including the cities of Washington, Georgetown, and Alexandria, under the exclusive control of Congress. Further, the unincorporated territory within the District was organized into two counties: the County of Washington to the east of the Potomac and the County of Alexandria to the west.[5] This Act formally established the borders of the area that would eventually become Arlington but the citizens located in the District were no longer considered residents of Maryland or Virginia, thus ending their representation in Congress.[6]

Retrocession[]

Residents of Alexandria County had expected the federal capital's location to result in land sales and the growth of commerce. Instead the county found itself struggling to compete with the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal at the port of Georgetown, which was farther inland and on the northern side of the Potomac River next to the City of Washington.[7] Members of Congress from other areas of Virginia also used their power to prohibit funding for projects, such as the Alexandria Canal, which would have increased competition with their home districts. In addition, Congress had prohibited the federal government from establishing any offices in Alexandria, which made the county less important to the functioning of the national government.[8]

Alexandria had also been a major market in the American slave trade, and rumors circulated that abolitionists in Congress were attempting to end slavery in the District; such an action would have further depressed Alexandria's slavery-based economy.[9] At the same time, an active abolitionist movement arose in Virginia that created a division on the question of slavery in the Virginia General Assembly. Pro-slavery Virginians recognized that if Alexandria were returned to the Commonwealth, it could provide two new representatives who favored slavery in the state legislature. During the American Civil War, this division led to the formation of the state of West Virginia, which comprised the 61 counties in the northwest that favored abolitionism.[10]

Largely as a result of the economic neglect by Congress, divisions over slavery, and the lack of voting rights for the residents of the District, a movement grew to separate Alexandria County from the District of Columbia. From 1840 to 1846, Alexandrians petitioned Congress and the Virginia legislature to approve this transfer known as retrocession. On February 3, 1846, the Virginia General Assembly agreed to accept the retrocession of Alexandria if Congress approved. Following additional lobbying by Alexandrians, Congress passed legislation on July 9, 1846, to return all the District's territory south of the Potomac River back to the Commonwealth of Virginia, pursuant to a referendum; President Polk signed the legislation the next day. A referendum on retrocession was held on September 1–2, 1846. The residents of the City of Alexandria voted in favor of the retrocession, 734 to 116; however, the residents of Alexandria County voted against retrocession 106 to 29. Despite the objections of those living in Alexandria County, President Polk certified the referendum and issued a proclamation of transfer on September 7, 1846. However, the Virginia legislature did not immediately accept the retrocession offer. Virginia legislators were concerned that the people of Alexandria County had not been properly included in the retrocession proceedings. After months of debate, the Virginia General Assembly voted to formally accept the retrocession legislation on March 13, 1847.[8] In 1852, the Virginia legislature voted to incorporate a portion of Alexandria County to make the City of Alexandria, which until then had been only been considered politically as a town.[11]

Arlington National Cemetery sits on land confiscated from Confederate General Robert E. Lee.

Civil War[]

During the American Civil War, Virginia seceded from the Union as a result of a statewide referendum held on May 23, 1861; the voters from Alexandria County approved secession by a vote of 958-48. This vote indicates the degree to which its only town, Alexandria was pro-secession and pro-Confederate. The Union loyalists who lived in rural areas outside the town of Alexandria, rejected secession.[12] Though Virginia was part of the Confederacy, its control did not extend all the way through Northern Virginia. The United States Congress passed a law in 1862 that those districts in which the "insurrection" persisted were to pay their real estate taxes in person. The property of Confederate General Robert E. Lee at Custis-Lee Mansion was subjected to an appraisal of $26,810 on which a tax of $92.07 was assessed. The Lees could not pay this in person as they would be subject to arrest. The property was then confiscated by the Federal government as a result and made into a soldier's cemetery. After the war, and after the deaths of the Lees (Robert E. Lee died in 1870), the United States Supreme Court found that the confiscation had been unconstitutional and the United States Government paid the Lee family $150,000 for the value of the property.[13] Today, the Arlington House is maintained as an historic site at present-day Arlington National Cemetery.

Confederate incursions from Falls Church, Minor's Hill and Upton's Hill—-then securely in Confederate hands—-occurred as far east as the present-day area of Ballston. On August 17, 1861 an armed force of 600 Confederate soldiers engaged the 23rd New York Infantry near that crossroads, killing one. Another large incursion on August 27 involved between 600 and 800 Confederate soldiers, which clashed with Union soldiers at Ball’s Crossroads, Hall’s Hill and along the modern-day border between the City of Falls Church and Arlington. A number of soldiers on both sides were killed. However, the territory in present-day Arlington was never successfully captured by Confederate forces.[14]

20th century[]

In 1896 an electric trolley line was built from Washington through Ballston, which lead to growth in the county. In 1920, the Virginia legislature renamed the area Arlington County to avoid confusion with the City of Alexandria which had become an independent city in 1870 under the new Virginia Constitution adopted after the Civil War. In the 1930s Hoover Field was established on the present site of the Pentagon; in that decade, Buckingham, Colonial Heights, and other apartment communities also opened. World War II brought a boom to the county, but one that could not be met by new construction due to rationing imposed by the war effort. In October 1942, not a single rental unit was available in the county.[15] The Henry G. Shirley Highway (now Interstate 395) was constructed during World War II, along with adjacent developments such as Shirlington, Fairlington, and Parkfairfax.

The attacks of 9/11 killed 125 people at The Pentagon.

Geography[]

Aerial view of a growth pattern in Arlington County, Virginia. High density, mixed use development is often concentrated within 1/4 to 1/2 mile from the County's Metrorail rapid transit stations, such as in Rosslyn, Courthouse, and Clarendon (shown in red from upper left to lower right).

Arlington County is located at Coordinates: and is surrounded by Fairfax County and the Falls Church to the southwest, the City of Alexandria to the southeast, and Washington, D.C. to the northeast directly across the Potomac River, which forms the county's northern border. Other landforms also form county borders, particularly Minor's Hill and Upton's Hill on the west.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 26 square miles (67.3 km2), of which about 4.6 square miles (11.9 km2) is federal property. The county is roughly in the shape of a rectangle 4 miles (6.4 km) by 6 miles (9.7 km), with the small end slanting in a northwest-southeast direction. All cities within the Commonwealth of Virginia are independent of counties, though towns may be incorporated within counties. However, Arlington has no existing incorporated towns because Virginia law prevents the creation of any new municipality within a county that has a population density greater than 1,000 persons per square mile. Its county seat is the census-designated place (CDP) of Arlington,[16] which is coterminous with the boundaries of the county; however, the county courthouse and most government offices are located in the Courthouse neighborhood.

There are a number of unincorporated neighborhoods within Arlington that are commonly referred to by name as if they were distinct towns. For over 30 years, the government has pursed a development strategy of concentrating much of its new development near transit facilities, such as Metrorail stations and the high-volume bus lines of Columbia Pike.[17] Within the transit areas, the government has a policy of encouraging mixed-use and pedestrian- and transit-oriented development.[18] Some of these "urban village" communities include:

|

|

|

|

In 2002, Arlington received the EPA's National Award for Smart Growth Achievement for "Overall Excellence in Smart Growth."[19] In 2005, the County implemented an affordable housing ordinance that requires most developers to contribute significant affordable housing resources, either in units or through a cash contribution, in order to obtain the highest allowable amounts of increased building density in new development projects, most of which are planned near Metrorail station areas.[20]

A number of the county's residential neighborhoods and larger garden-style apartment complexes are listed in the National Register of Historic Places and/or designated under the County government's zoning ordinance as local Historic Preservation Districts.[21][22] These include Arlington Village, Arlington Forest, Ashton Heights, Buckingham, Cherrydale, Claremont, Colonial Village, Fairlington, Lyon Park, Lyon Village, Maywood, Penrose, Waverly Hills and Westover.[23][24] Many of Arlington County's neighborhoods participate in the Arlington County government's Neighborhood Conservation Program (NCP).[25] Each of these neighborhoods has a Neighborhood Conservation Plan that describes the neighborhood's characteristics, history and recommendations for capital improvement projects that the County government funds through the NCP.[26]

Demographics[]

| Historical populations | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1800 | 5,949 | ||

| 1810 | 8,552 | 43.8% | |

| 1820 | 9,703 | 13.5% | |

| 1830 | 9,573 | −1.3% | |

| 1840 | 9,967 | 4.1% | |

| 1850 | 10,008 | 0.4% | |

| 1860 | 12,652 | 26.4% | |

| 1870 | 16,755 | 32.4% | |

| 1880 | 17,546 | 4.7% | |

| 1890 | 18,597 | 6.0% | |

| 1900 | 6,430 | −65.4% | |

| 1910 | 10,231 | 59.1% | |

| 1920 | 16,040 | 56.8% | |

| 1930 | 26,615 | 65.9% | |

| 1940 | 57,040 | 114.3% | |

| 1950 | 135,449 | 137.5% | |

| 1960 | 163,401 | 20.6% | |

| 1970 | 174,284 | 6.7% | |

| 1980 | 152,599 | −12.4% | |

| 1990 | 170,936 | 12.0% | |

| 2000 | 189,453 | 10.8% | |

| 2010 | 207,627 | 9.6% | |

The United States Census Bureau found that there were 207,627 residents as of April 1, 2010.[27]

As of the 2000 census[28], there were:

- 189,453 people

- 86,352 households,

- and 39,290 families residing in Arlington.

The population density was 7,323 people per square mile (2,828/km²), the highest of any county in Virginia.[29] There were 90,426 housing units at an average density of 3,495/sq mi (1,350/km²).

In 2010, the racial makeup of the county was 64.04% non-Hispanic White, 8.23% Non-Hispanic Black or African American, 0.20% Non-Hispanic Native American, 9.52% Non-Hispanic Asian, 0.08% Pacific Islander, 0.29% Non-Hispanic other races, 2.55% Non-Hispanics reporting two or more race. Hispanics or Latinos made up 15.11% of the county's population.[30] 28% of Arlington residents were foreign-born as of 2000.

The recently completed Waterview towers in Rosslyn as seen from Theodore Roosevelt Island in the Potomac river.

There were 86,352 households out of which 19.30% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 35.30% were married couples living together, 7.00% had a female householder with no husband present, and 54.50% were non-families. 40.80% of all households were made up of individuals and 7.30% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.15 and the average family size was 2.96.

Families headed by single parents was the lowest in the DC area, under 6%, as estimated by the Census Bureau for the years 2006-2008. For the same years, the percentage of people estimated to be living alone was the third highest in the DC area, at 45%.[31]

According to a 2007 estimate, the median income for a household in the county was $94,876, and the median income for a family was $127,179.[32] Males had a median income of $51,011 versus $41,552 for females. The per capita income for the county was $37,706. About 5.00% of families and 7.80% of the population were below the poverty line, including 9.10% of those under age 18 and 7.00% of those age 65 or over.

In 2009, the county was second in the nation (after nearby Loudoun County) for the percentage of people ages 25–34 earning over $100,000 annually (8.82% of the population).[33] [34]

In 2009, Arlington was highest in the Washington DC Metropolitan area for percentage of people who were single - 70.9%. 14.3% were married. 14.8% had families.[33]

The age distribution was 16.50% under 18, 10.40% from 18 to 24, 42.40% from 25 to 44, 21.30% from 45 to 64, and 9.40% who were 65 or older. The median age was 34 years. For every 100 females there were 101.50 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 100.70 males.

CNN Money ranked Arlington as the most educated city in 2006 with 35.7% of residents having held graduate degrees. Along with five other counties in Northern Virginia, Arlington ranked among the twenty American counties with the highest median household income in 2006.[35] In July 2009, CNN Money ranked Arlington second in the country in its listing of "Best Places for the Rich and Single."[36]

In 2008, 20.3% of the population did not have medical health insurance.[37]

In 2010, AIDS prevalence was 341.5 per 100,000 population. This was eight times the rate of nearby Loudoun County and one-quarter the rate of the District of Columbia.[38]

Crime statistics for 2009 included the report of 2 homicides, 15 forcible rapes, 149 robberies, 145 incidents of or aggravated assault, 319 burglaries, 4,140 incidents of larceny, and 297 reports of vehicle theft. This was a reduction in all categories from the previous year.[39]

Government and politics[]

Local government[]

| Position | Name | Party | First elected | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| style="background-color:#3333FF;" width=10px | " | | Vice Chair | Katie Cristol[40] | Democratic | 2015 |

| style="background-color:#3333FF;" width=10px | " | | Chair | Matt de Ferranti[41] | Democratic | 2018 |

| style="background-color:#3333FF;" width=10px | " | | Member | Christian Dorsey[42] | Democratic | 2015 |

| style="background-color:#3333FF;" width=10px | " | | Member | Libby Garvey[43] | Democratic | 2012 |

| style="background-color:#3333FF;" width=10px | " | | Member | Takis Karantonis[44] | Democratic | 2020 |

The county is governed by a five-person County Board; members are elected at-large on staggered four-year terms. They appoint a county manager, who is the chief executive of the County Government. Like all Virginia counties, Arlington has five elected constitutional officers: a clerk of court, a commissioner of revenue, a commonwealth's attorney, a sheriff, and a treasurer. The budget for the fiscal year 2009 was $1.177 billion.[45]

| Position | Name | Party | First elected | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| style="background-color:#3333FF;" width=10px | " | | Clerk of the Circuit Court | Paul Ferguson[46] | Democratic | 2007 |

| style="background-color:#3333FF;" width=10px | " | | Commissioner of Revenue | Ingrid Morroy[47] | Democratic | 2003 |

| style="background-color:#3333FF;" width=10px | " | | Commonwealth's Attorney | Parisa Dehghani-Tafti[48] | Democratic | 2019 |

| style="background-color:#3333FF;" width=10px | " | | Sheriff | Beth Arthur[49] | Democratic | 2000 |

| style="background-color:#3333FF;" width=10px | " | | Treasurer | Carla de la Pava[50] | Democratic | 2014 |

For the last two decades, Arlington has been a Democratic stronghold at nearly all levels of government.[51] However, during a special election in April 2014, a Republican running as an independent, John Vihstadt, captured a County Board seat, defeating Democrat Alan Howze 57% to 41%; he became the first non-Democratic board member in fifteen years.[52] This was in large part a voter response to plans to raise property taxes to fund several large projects, including a streetcar and an aquatics center. County Board Member Libby Garvey, in April 2014, resigned from the Arlington Democratic Committee after supporting Vihstadt's campaign over Howze.[53] Eight months later, in November's general election, Vihstadt won a full term; winning by 56% to 44%.[54] This is the first time since 1983 that a non-Democrat won a County Board general election.[55]

Incorporation[]

Under Virginia law, the only municipalities that may be contained within counties are incorporated towns; incorporated cities are independent of any county. Arlington, despite its population density and largely urban character, is wholly unincorporated with no towns inside its borders. In the 1920s, a group of citizens petitioned the state courts to incorporate the Clarendon neighborhood as a town, but this was rejected; the Supreme Court of Virginia held, in Bennett v. Garrett (1922), that Arlington constituted a "continuous, contiguous, and homogeneous community" that should not be subdivided through incorporation.[56]

Current state law would prohibit the incorporation of any towns within the county because the county's population density exceeds 200 persons per square mile.[57] In 2017, then-county board chairman Jay Fisette suggested that the county as a whole should incorporate as an independent city.[58]

State and federal elections[]

In 2009, Republican Attorney General Bob McDonnell won Virginia by a 59% to 41% margin, but Arlington voted 66% to 34% for Democratic State Senator Creigh Deeds.[59] Turnout was 42.78%.[60]

Arlington elects four members of the Virginia House of Delegates and two members of the Virginia State Senate. State Senators are elected for four-year terms, while Delegates are elected for two-year terms.

In the Virginia State Senate, Arlington is split between the 30th, 31st, and 32nd districts, represented by Adam Ebbin, Barbara Favola, and Janet Howell, respectively. In the Virginia House of Delegates, Arlington is divided between the 45th, 47th, 48th, and 49th districts, represented by Mark Levine, Patrick Hope, Rip Sullivan, and Alfonso Lopez, respectively. All are Democrats.

Arlington is part of Virginia's 8th congressional district, represented by Democrat Don Beyer.

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third party | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| 2020 | 22,318 | 17.08% | 105,344 | 80.60% | 3,037 | 2.32% |

| 2016 | 20,186 | 16.64% | 92,016 | 75.83% | 9,137 | 7.53% |

| 2012 | 34,474 | 29.31% | 81,269 | 69.10% | 1,865 | 1.59% |

| 2008 | 29,876 | 27.12% | 78,994 | 71.71% | 1,283 | 1.16% |

| 2004 | 29,635 | 31.31% | 63,987 | 67.60% | 1,028 | 1.09% |

| 2000 | 28,555 | 34.17% | 50,260 | 60.15% | 4,744 | 5.68% |

| 1996 | 26,106 | 34.63% | 45,573 | 60.46% | 3,697 | 4.90% |

| 1992 | 26,376 | 31.94% | 47,756 | 57.83% | 8,452 | 10.23% |

| 1988 | 34,191 | 45.37% | 40,314 | 53.49% | 860 | 1.14% |

| 1984 | 34,848 | 48.24% | 37,031 | 51.26% | 363 | 0.50% |

| 1980 | 30,854 | 46.15% | 26,502 | 39.64% | 9,505 | 14.22% |

| 1976 | 30,972 | 47.95% | 32,536 | 50.37% | 1,091 | 1.69% |

| 1972 | 39,406 | 59.36% | 25,877 | 38.98% | 1,100 | 1.66% |

| 1968 | 28,163 | 45.92% | 26,107 | 42.57% | 7,056 | 11.51% |

| 1964 | 20,485 | 37.68% | 33,567 | 61.75% | 311 | 0.57% |

| 1960 | 23,632 | 51.40% | 22,095 | 48.06% | 250 | 0.54% |

| 1956 | 21,868 | 55.05% | 16,674 | 41.97% | 1,183 | 2.98% |

| 1952 | 22,158 | 60.91% | 14,032 | 38.57% | 190 | 0.52% |

| 1948 | 10,774 | 53.57% | 7,798 | 38.77% | 1,539 | 7.65% |

| 1944 | 8,317 | 53.66% | 7,122 | 45.95% | 60 | 0.39% |

| 1940 | 4,365 | 44.26% | 5,440 | 55.16% | 57 | 0.58% |

| 1936 | 2,825 | 36.06% | 4,971 | 63.45% | 39 | 0.50% |

| 1932 | 2,806 | 45.01% | 3,285 | 52.69% | 143 | 2.29% |

| 1928 | 4,274 | 74.75% | 1,444 | 25.25% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1924 | 1,307 | 44.74% | 1,209 | 41.39% | 405 | 13.87% |

| 1920 | 997 | 53.32% | 835 | 44.65% | 38 | 2.03% |

| 1916 | 412 | 43.37% | 515 | 54.21% | 23 | 2.42% |

| 1912 | 125 | 15.45% | 394 | 48.70% | 290 | 35.85% |

| 1908 | 165 | 31.61% | 354 | 67.82% | 3 | 0.57% |

| 1904 | 99 | 38.52% | 157 | 61.09% | 1 | 0.39% |

| 1900 | 421 | 50.36% | 413 | 49.40% | 2 | 0.24% |

| 1896 | 713 | 68.62% | 322 | 30.99% | 4 | 0.38% |

| 1892 | 1,069 | 46.52% | 1,169 | 50.87% | 60 | 2.61% |

| 1888 | 462 | 63.64% | 255 | 35.12% | 9 | 1.24% |

| 1884 | 509 | 65.85% | 264 | 34.15% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1880 | 489 | 64.85% | 265 | 35.15% | 0 | 0.00% |

| Year | Democratic | Republican |

|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 66.2% 54,651 | 33.8% 27,871 |

| 2002 | 73.4% 36,508 | |

| 2006 | 72.6% 53,021 | 26.3% 19,200 |

| 2008 | 76.0% 82,119 | 22.4% 24,232 |

| 2012 | 71.4% 82,689 | 28.3% 32,807 |

| 2014 | 70.5% 47,709 | 27.0% 18,239 |

| 2018 | 81.6% 87,258 | 15.4% 16,495 |

| 2020 | 79.4% 102,880 | 20.5% 26,590 |

| Year | Democratic | Republican |

|---|---|---|

| 1993 | 63.3% 32,736 | 36.2% 18,719 |

| 1997 | 62.0% 30,736 | 36.8% 18,252 |

| 2001 | 68.3% 35,990 | 30.8% 16,214 |

| 2005 | 74.3% 42,319 | 23.9% 13,631 |

| 2009 | 66.5% 36,949 | 34.3% 19,325 |

| 2013 | 71.6% 48,346 | 22.2% 14,978 |

| 2017 | 79.9% 68,093 | 19.0% 16,268 |

| 2021 | 76.67% 73,013 | 22.63% 21,548 |

The United States Postal Service designates zip codes starting with "222" for exclusive use in Arlington County. However, federal institutions, like Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport and The Pentagon use Washington zip codes.

Economy[]

DARPA headquarters in the Virginia Square neighborhood.

Park Four, former US Airways headquarters in Crystal City

Some low-rise residential structures also help make up the real estate inventory in Arlington.

Arlington has consistently had the lowest unemployment rate of any jurisdiction in Virginia.[64] The unemployment rate in Arlington was 4.2% in August 2009.[65] 60% of office space in the Rosslyn-Ballston corridor is leased to government agencies and government contractors.[66] There were an estimated 205,300 jobs in the county in 2008. About 28.7% of these were with the federal, state or local government; 19.1% technical and professional; 28.9% accommodation, food and other services.[67]

In October 2008, BusinessWeek ranked Arlington as the safest city in which to weather a recession, with a 49.4% share of jobs in "strong industries".[68] In October 2009, during the economic downturn, the unemployment in the county reached 4.2%. This was the lowest in the state, which averaged 6.6% for the same time period, and among the lowest in the nation, which averaged 9.5% for the same time.[69]

In 2010, there were an estimated 90,842 residences in the county.[70] In 2000, the median single family home price was $262,400. About 123 homes were worth $1 million or more. In 2008, the median home was worth $586,200. 4,721 houses, about 10% of all stand-alone homes, were worth $1 million or more.[71]

In 2010, there were 0.9 percent of the homes in foreclosure. This was the lowest rate in the DC area.[72]

A number of federal agencies are headquartered in Arlington, including the Air Force Office of Scientific Research, DARPA, Drug Enforcement Administration, Foreign Service Institute, National Science Foundation, Office of Naval Research, Transportation Security Administration, United States Department of Defense, United States Fish and Wildlife Service, United States Marshals Service, and the United States Trade and Development Agency.

Companies headquartered in Arlington include AES, Allbritton Communications Company, Alcalde and Fay, Arlington Asset Investment, CACI, Corporate Executive Board, ENVIRON International Corporation, ESI International, FBR Capital Markets, Interstate Hotels & Resorts, Rosetta Stone and Strayer Education.

Organizations located here include Associated General Contractors, The Conservation Fund, Conservation International, the Consumer Electronics Association, The Fellowship, the Feminist Majority Foundation, the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association, The Nature Conservancy, the Public Broadcasting Service, United Service Organizations and the US-Taiwan Business Council.

According to the County's 2009 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[73] the top employers in the county are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Virginia Hospital Center | 2,354 |

| 2 | Corporate Executive Board | 1,534 |

| 3 | US Airways Group | 1,472 |

| 4 | Lockheed Martin | 1,453 |

| 5 | Marriott International | 1,450 |

| 6 | BAE Systems | 1,407 |

| 7 | Booz Allen Hamilton | 1,384 |

| 8 | SRA International | 1,283 |

| 9 | SAIC | 1,257 |

| 10 | CACI | 1,198 |

| 11 | Bureau of National Affairs | 900 |

| 12 | Verizon | 790 |

| 13 | Marymount University | 637 |

| 14 | Boeing | 545 |

| 15 | Cambridge Associates | 520 |

| 16 | Macy's | 507 |

| 17 | Interstate Hotels & Resorts | 501 |

| 18 | Towers Watson | 500 |

| 19 | National Rural Electric Cooperative Association | 500 |

| 20 | Jacobs | 500 |

Landmarks[]

Arlington National Cemetery[]

Arlington National Cemetery is an American military cemetery established during the American Civil War on the grounds of Confederate General Robert E. Lee's home, Arlington House (also known as the Custis-Lee Mansion). It is directly across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C., north of the Pentagon. With nearly 300,000 people buried there, Arlington National Cemetery is the second-largest national cemetery in the United States.

Iwo Jima Memorial

Arlington House was named after the Custis family's homestead on Virginia's Eastern Shore. It is associated with the families of Washington, Custis, and Lee. Begun in 1802 and completed in 1817, it was built by George Washington Parke Custis. After his father died, young Custis was raised by his grandmother and her second husband, the first US President George Washington, at Mount Vernon. Custis, a far-sighted agricultural pioneer, painter, playwright, and orator, was interested in perpetuating the memory and principles of George Washington. His house became a "treasury" of Washington heirlooms.

In 1804, Custis married Mary Lee Fitzhugh. Their only child to survive infancy was Mary Anna Randolph Custis, born in 1808. Young Robert E. Lee, whose mother was a cousin of Mrs. Custis, frequently visited Arlington. Two years after graduating from West Point, Lieutenant Lee married Mary Custis at Arlington on June 30, 1831. For 30 years, Arlington House was home to the Lees. They spent much of their married life traveling between U.S. Army duty stations and Arlington, where six of their seven children were born. They shared this home with Mary's parents, the Custis family.

When George Washington Parke Custis died in 1857, he left the Arlington estate to Mrs. Lee for her lifetime and afterward to the Lees' eldest son, George Washington Custis Lee.

The U.S. government confiscated Arlington House and 200 acres (81 hectares) of ground immediately from the wife of General Robert E. Lee during the Civil War. The government designated the grounds as a military cemetery on June 15, 1864, by Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton. In 1882, after many years in the lower courts, the matter of the ownership of Arlington National Cemetery was brought before the United States Supreme Court. The Court decided that the property rightfully belonged to the Lee family. The United States Congress then appropriated the sum of $150,000 for the purchase of the property from the Lee family.

Veterans from all the nation's wars are buried in the cemetery, from the American Revolution through the military actions in Afghanistan and Iraq. Pre-Civil War dead were re-interred after 1900.

The Tomb of the Unknowns, also known as the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, stands atop a hill overlooking Washington, DC. President John F. Kennedy is buried in Arlington National Cemetery with his wife and some of their children. His grave is marked with an "Eternal Flame." His brothers, Senators Robert F. Kennedy and Edward M. Kennedy, are also buried nearby. Another President, William Howard Taft, who was also a Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, is the only other President buried at Arlington.

Other frequently visited sites near the cemetery are the U.S. Marine Corps War Memorial, commonly known as the "Iwo Jima Memorial", the U.S. Air Force Memorial, the Women in Military Service for America Memorial, the Netherlands Carillon and the U.S. Army's Fort Myer.

The Pentagon[]

The Pentagon, looking northeast with the Potomac River and Washington Monument in the distance.

The Pentagon Memorial and Air Force Memorial.

The Pentagon in Arlington is the headquarters of the United States Department of Defense. It was dedicated on January 15, 1943 and it is the world's largest office building. Although it is located in Arlington, the United States Postal Service requires that "Washington, D.C." be used as the place name in mail addressed to the six ZIP codes assigned to The Pentagon.[74]

The building is pentagon-shaped in plan and houses about 23,000 military and civilian employees and about 3,000 non-defense support personnel. It has five floors and each floor has five ring corridors. The Pentagon's principal law enforcement arm is the United States Pentagon Police, the agency that protects the Pentagon and various other DoD jurisdictions throughout the National Capital Region.

Built during the early years of World War II, it is still thought of as one of the most efficient office buildings in the world. It has 17.5 miles (28 km) of corridors, yet it takes only seven minutes or so to walk between any two points in the building.

It was built from 680,000 short tons (620,000 t) of sand and gravel dredged from the nearby Potomac River that were processed into 435,000 cubic yards (330,000 m³) of concrete and molded into the pentagon shape. Very little steel was used in its design due to the needs of the war effort.

The open-air central plaza in the Pentagon is the world's largest "no-salute, no-cover" area (where U.S. servicemembers need not wear hats nor salute). The snack bar in the center is informally known as the Ground Zero Cafe, a nickname originating during the Cold War when the Pentagon was targeted by Soviet nuclear missiles.

During World War II, the earliest portion of the Henry G. Shirley Memorial Highway was built in Arlington in conjunction with the parking and traffic plan for the Pentagon. This early freeway, opened in 1943, and completed to Woodbridge, Virginia in 1952, is now part of Interstate 395.

Transportation[]

Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport

Pentagon City station, which is directly connected to the Pentagon City mall.

Arlington forms part of region's core transportation network. The county is traversed by two interstate highways, Interstate 66 in the northern part of the county and Interstate 395 in the eastern part, both with high-occupancy vehicle lanes or restrictions. In addition, the county is served by the George Washington Memorial Parkway. In total, Arlington County maintains 376 miles (605 km) of roads.[75]

The street names in Arlington generally follow a unified countywide convention. The north-south streets are generally alphabetical, starting with one-syllable names, then two-, three- and four-syllable names. The "lowest" alphabetical street is Ball Street. The "highest" is Arizona. Many east-west streets are numbered. Route 50 divides Arlington County. Streets are generally labeled North above Route 50, and South below.

Arlington is served by the Orange, Blue and Yellow lines of the Washington Metro. Additionally, it is served by Virginia Railway Express commuter rail, Metrobus (regional public bus), Fairfax Connector (regional public bus), Potomac and Rappahannock Transportation Commission (PRTC) (regional public bus), and a county public bus system, Arlington Transit (ART).

Arlington County is home to Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport, which provides domestic air services to the Washington, D.C. area. In 2009, Condé Nast Traveler readers voted it the country's best airport.[76] Nearby international airports are Washington Dulles International Airport, located in Fairfax and Loudoun counties in Virginia, and Baltimore-Washington International Thurgood Marshall Airport, located in Anne Arundel County, Maryland.

Several hybrid taxis at Pentagon City. The taxicab with the white and green livery is operated by EnviroCAB, the first all-hybrid taxicab fleet in the US.

In 2007, the county authorized EnviroCAB, a new taxi company, to operate exclusively with a hybrid-electric fleet of 50 vehicles and also issued permits for existing companies to add 35 hybrid cabs to their fleets. As operations began in 2008, EnvironCab became the first all-hybrid taxicab fleet in the U.S. and the company not only offsets the emissions generated by its fleet of hybrids, but also the equivalent emissions of 100 non-hybrid taxis in service in the metropolitan area.[77][78] The green taxi expansion is part of a county campaign known as Fresh AIRE, or Arlington Initiative to Reduce Emissions, that aims to cut production of greenhouse gases from county buildings and vehicles by 10 percent by 2012.[77]

Arlington has a bicycle sharing service provided by Capital Bikeshare. Shown the rental site located near Pentagon City Metro station.

Arlington has 86 miles (138 km) of on-street and paved off-road bicycle trails.[79] Off-road trails travel along the Potomac River or its tributaries, abandoned railroad beds, or major highways, including: Four Mile Run Trail that travels the length of the county; the Custis Trail, which runs the width of the county from Rosslyn; the Washington & Old Dominion Railroad Trail (W&OD Trail) that travels 45 miles (72 km) from the Shirlington neighborhood out to western Loudoun County; the Mount Vernon Trail that runs for 17 miles (27 km) along the Potomac, continuing through Alexandria to Mount Vernon.

Capital Bikeshare, a bicycle sharing system, began operations in September 2010 with 14 rental locations primarily around Washington Metro stations in throughout the county.[80]

Education[]

Arlington Public Schools operates the county's public K-12 education system of 22 elementary schools, 5 middle schools, and 4 public high schools in Arlington County including Wakefield High School, Washington-Lee High School, Yorktown High School and the H-B Woodlawn alternative school. Arlington County spends about half of its local revenues on education, making it one of the top ten per-pupil spenders in the nation. As of 2004, over $13,000, the second highest amount spent on education in the United States, behind New York City.

Arlington has an elected five-person school board whose members are elected to four year terms. Virginia law does not permit political parties to place school board candidates on the ballot.[81]

| Position | Name | First Election | Next Election |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chair | Sally Baird | 2006 | 2010 |

| Vice Chair | Libby Garvey | 1996 | 2012 |

| Member | James Lander | 2009 | 2013 |

| Member | Abby Raphael | 2007 | 2011 |

| Member | Emma Sanchez-Violand | 2008 | 2012 |

Through an agreement with Fairfax County Public Schools approved by the school board in 1999, up to 26 students residing in Arlington per grade level may be enrolled at the Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology in Fairfax at a cost to Arlington of approximately $8000 per student. For the first time in 2006, more students (36) were offered admission in the selective high school than allowed by the previously established enrollment cap.[82]

The George Mason University School of Law

Marymount University is the only university with its main campus located in Arlington. Founded in 1950 by the Religious of the Sacred Heart of Mary as Marymount College of Virginia located on North Glebe Road. George Mason University operates an Arlington campus in the Virginia Square area between Clarendon and Ballston. The campus houses the George Mason University School of Law, School of Public Policy and other programs.

Other private and technical schools maintain a campus in Arlington, including the Institute for the Psychological Sciences, the John Leland Center for Theological Studies, the University of Management and Technology, The Art Institute of Washington, DeVry University. Strayer University has a campus in Arlington as well as its corporate headquarters.

In addition, Argosy University, Banner College, Everest College, George Washington University, Georgetown University, Northern Virginia Community College, Troy University, the University of New Haven, the University of Oklahoma, and Westwood College all have campuses in Arlington.

Sister cities[]

Arlington has four sister cities, as designated by Sister Cities International: [83]

Notable residents[]

- Robert E. Lee, Confederate general who lived at Arlington House

- George Washington Parke Custis, orator and playwright, the step-grandson and adopted son of President George Washington

- David McDowell Brown, NASA astronaut, died during Shuttle Columbia mission STS-107

- Sandra Bullock, movie actress

- Aldrich Hazen Ames[84]

- Major Nidal Malik Hasan, the sole suspect in the November 5, 2009 Fort Hood shootings. Born in Arlington.[85]

- Katie Couric, Journalist, CBS News Anchor, Interviewer

- Warren Beatty, actor and director

- Shirley MacLaine, actress

- Tom Dolan, Olympic swimmer

- Patch Adams

- Connor Barth, Kicker for the Tampa Bay Buccaneers

- Zac Hanson

- Alexander Ovechkin, NHL player with the Washington Capitals

- Danny Ahn, musician

- Mikhail Kutzik and Natalia Pereverzeva - accused spies

- Dave Batista, former WWE professional wrestler

See also[]

- Arlington Hall

- Arlington Independent Media

- List of federal agencies in Northern Virginia

- List of people from the Washington, D.C. metropolitan area

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Arlington County, Virginia

References[]

- ^ Nathanielturner.com

- ^ Crew, Harvey W.; William Bensing Webb, John Wooldridge (1892). Centennial History of the City of Washington, D. C.. Dayton, Ohio: United Brethren Publishing House. pp. 89–92. http://books.google.com/?id=5Q81AAAAIAAJ.

- ^ United States Statutes At Large, 1st Congress, Session III, Chapter 18, pp. 214-215, March 3, 1791.

- ^ "Boundary Stones of Washington, D.C.". BoundaryStones.org. http://www.boundarystones.org/. Retrieved May 27, 2008.

- ^ Crew, Harvey W.; William Bensing Webb, John Wooldridge (1892). "IV. Permanent Capital Site Selected". Centennial History of the City of Washington, D. C.. Dayton, Ohio: United Brethren Publishing House. p. 103. http://books.google.com/?id=5Q81AAAAIAAJ.

- ^ "Statement on the subject of The District of Columbia Fair and Equal Voting Rights Act" (PDF). American Bar Association. September 14, 2006. http://www.abanet.org/poladv/letters/electionlaw/060914testimony_dcvoting.pdf. Retrieved July 10, 2008.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions About Washington, D.C". Historical Society of Washington, D.C.. http://www.historydc.org/aboutdc.aspx. Retrieved 2010-10-03.

- ^ a b Richards, Mark David (Spring/Summer 2004). "The Debates over the Retrocession of the District of Columbia, 1801–2004". Washington History: 54–82. Retrieved on 2009-01-16.

- ^ Greeley, Horace (1864). The American Conflict: A History of the Great Rebellion in the United States. Chicago: G. & C.W. Sherwood. pp. 142–144. http://books.google.com/?id=ZlIMAAAAYAAJ.

- ^ Richards, Mark David (Spring/Summer 2004). "The Debates over the Retrocession of the District of Columbia, 1801–2004". Washington History: 54–82. Retrieved on January 16, 2009.

- ^ "Alexandria's History". http://alexandriava.gov/city/about-alexandria/about.html#history. Retrieved August 30, 2006.

- ^ Bradley E. Gernand. A Virginia Village Goes to War--Falls Church During the Civil War. Virginia Beach: The Donning Company, 2002. Page 23.

- ^ "Historical Information". Arlington National Cemetery. http://www.arlingtoncemetery.org/historical_information/arlington_house.html. Retrieved 2008-05-20.

- ^ Gernand, A Virginia Village Goes to War, pp. 73-74, 89.

- ^ Arlington Sun Gazette, October 15, 2009, "Arlington history", page 6, quoting from the Northern Virginia Sun

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. http://www.naco.org/Counties/Pages/FindACounty.aspx. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- ^ Smart Growth : Planning Division : Arlington, Virginia

- ^ http://www.arlingtonva.us/departments/CPHD/planning/powerpoint/rbpresentation/rbpresentation_060107.pdf

- ^ Arlington County, Virginia - National Award for Smart Growth Achievement - 2002 Winners Presentation

- ^ Housing Development - Affordable Housing Ordinance : Housing Division : Arlington, Virginia

- ^ Arlington County Government Historic Preservation Program Official Arlington County Government Website. Retrieved on 2008-02-05.

- ^ Arlington County Zoning Ordinance: Section 31.A. Historic Preservation Districts Official Arlington County Government Website. Retrieved on 2008-02-05.

- ^ List of Arlington County Government Designated Local Historic Districts Official Arlington County Government Website. Retrieved on 2008-02-05.

- ^ List of Arlington County Sites in the National Register of Historic Places Official Arlington County Government Website. Retrieved on 2008-02-05.

- ^ Neighborhood Conservation Program Official Arlington County Government Website. Retrieved on 2008-02-05.

- ^ Neighborhood Conservation Plans Official Arlington County Government Website. Retrieved on 2008-02-05.

- ^ [1]. 2010 U.S. Census Data: Virginia. Retrieved February 16, 2011

- ^ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. http://factfinder.census.gov. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ^ Arlington County Virginia - Geography

- ^ Census chart on ethnic and racial makeup of the population of Arlington County

- ^ Carol Morello; Dan Keating (2009-10-28). "Single living surges across D.C. region". Washington Post. Washington Post. pp. A20. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/10/27/AR2009102702019.html.

- ^ Arlington CDP, Virginia

- ^ a b Annie Gowen (2009-11-07). "Fresh faces, thick wallets". Washington Post. Washington Post. pp. B4. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/11/06/AR2009110604170.html.

- ^ The highest was Loudoun County, Virginia

- ^ Woolsey, Matt (2008-01-22). "Real Estate: America's Richest Counties". Forbes.com. http://www.forbes.com/2008/01/22/counties-rich-income-forbeslife-cx_mw_0122realestate.html. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ^ "Best Places for the Rich and Single" Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- ^ Hank Silverberg (2008-10-09). "Hundreds of thousands in region lack health insurance". WTOP FM Radio. WTOP FM Radio. http://www.wtop.com/?nid=720&sid=1493997.

- ^ Fears, Darryl (27 April 2010). "Suburbs trail D.C. in fighting AIDS, study ssays". Washington, DC: Washington Post. pp. A5. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/04/26/AR2010042604338.html.

- ^ "Violent Crime Down 8.3 Percent". Arlington, Virginia: The Arlington Connection. April 14–20, 2010. pp. 5. http://www.co.arlington.va.us/departments/Communications/PressReleases/page75824.aspx.

- ^ "Katie Cristol - County Board". County Board: Members. Arlingtonva.us. http://countyboard.arlingtonva.us/katie-cristol/.

- ^ "BREAKING: De Ferranti Bests Vihstadt for County Board, Amidst Democratic Sweep in Arlington". November 6, 2018. https://www.arlnow.com/2018/11/06/developing-spotlight-on-county-board-race-as-results-trickle-in/.

- ^ "Christian Dorsey - County Board". County Board: Members. Arlingtonva.us. http://countyboard.arlingtonva.us/christian-dorsey/.

- ^ "Libby Garvey, Arlington County Board biography". County Board: Members. Arlingtonva.us. http://countyboard.arlingtonva.us/county-board-members/libby-garvey/.

- ^ "BREAKING: Takis Karantonis Wins County Board Special Election In Landslide" (in en). 2020-07-07. https://www.arlnow.com/2020/07/07/breaking-takis-karantonis-wins-county-board-special-election-in-landslide/.

- ^ "Department of Management and Finance - Departments & Offices". Arlingtonva.us. http://www.arlingtonva.us/departments/ManagementAndFinance/budget/fy09adopted/C.2_Budget%20REsolution.pdf.

- ^ "Paul Ferguson, Clerk". Courts & Judicial Services. Arlingtonva.us. http://courts.arlingtonva.us/circuit-court/paul-ferguson/.

- ^ "Ingrid Morroy - Commissioner of Revenue". Newsroom. Arlingtonva.us. http://newsroom.arlingtonva.us/bios/ingrid-morroy/.

- ^ "Meet Parisa". Courts & Judicial Services. Arlingtonva.us. https://courts.arlingtonva.us/commonwealth-attorney/meet-parisa/.

- ^ "Beth Arthur - Sheriff". Newsroom. Arlingtonva.us. http://newsroom.arlingtonva.us/bios/beth-arthur/.

- ^ "Carla de la Pava - Treasurer". Newsroom. Arlingtonva.us. http://newsroom.arlingtonva.us/bios/carla-de-la-pava/.

- ^ "Arlington County Elected Officials". Voting & Elections. http://www.arlingtonva.us/departments/voterregistration/VoterRegistrationElected.aspx.

- ^ "Attorney John Vihstadt wins Arlington County Board seat; first non-Democrat since 1999". washingtonpost.com. https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/virginia-politics/attorney-john-vihstadt-wins-arlington-board-seat/2014/04/07/8537211a-be87-11e3-b195-dd0c1174052c_story.html.

- ^ "Garvey quits Arlington Democratic leadership over endorsement of Vihstadt over Howze". washingtonpost.com. https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/virginia-politics/garvey-quits-arlington-democratic-leadership-over-endorsement-of-vihstadt-over-howze/2014/04/29/160e4456-cfaf-11e3-b812-0c92213941f4_story.html?hpid=z3.

- ^ "John Vihstadt beats Democrat Alan Howze in race for Arlington County Board seat". washingtonpost.com. https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/virginia-politics/john-vihstadt-beats-democrat-alan-howze-in-race-for-arlington-county-board-seat/2014/11/04/ffd6bcd6-533e-11e4-892e-602188e70e9c_story.html?tid=hpModule_99d5f542-86a2-11e2-9d71-f0feafdd1394.

- ^ "Vihstadt Victory Could Signal Sea Change in Arlington Politics". arlnow.com. November 5, 2014. http://www.arlnow.com/2014/11/05/vihstadt-victory-could-signal-sea-change-in-arlington-politics/.

- ^ Office of the County Manager (Arlington, Virginia) (1967). "A History of the Boundaries of Arlington County, Virginia". http://www.gutenberg.org/files/36902/36902-h/36902-h.htm#27.

- ^ Peaslee, Liliokanaio; Swartz, Nicholas J. (2013-10-07) (in en). Virginia Government: Institutions and Policy. CQ Press. pp. 136–137. ISBN 978-1-4833-0146-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=nF92AwAAQBAJ&q=Bennett%20v.%20Garrett,%20112%20S.E.%20772&pg=PA137.

- ^ "No Longer A County Boy: Arlington Official Says County Should Become A City" (in en). https://wamu.org/story/17/07/14/no-longer-county-boy-arlington-official-says-county-become-city/.

- ^ Carl M. Cannon (November 4, 2009). "McDonnell, Republicans Sweep Virginia". Washington Post. pp. A1, A6. http://www.politicsdaily.com/2009/11/04/mcdonnell-republicans-sweep-virginia/.

- ^ "Northern Virginia Voter Turnout", Falls Church News-Press (Falls Church News Press): p. 5, November 5, 2009

- ^ Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". http://uselectionatlas.org/RESULTS.

- ^ Leip, David. "General Election Results – Virginia". United States Election Atlas. http://uselectionatlas.org/RESULTS/.

- ^ Leip, David. "Gubernatorial General Election Results". https://uselectionatlas.org/RESULTS/state.php?year=2021&fips=51&f=0&off=5&elect=0.

- ^ Arlington Unemployment Drops Below 4 Percent, Arlington Sun Gazette, December 4, 2009

- ^ Northern Virginia jobless rate falls to 5%

- ^ An Oasis of Stability Amid a Downturn

- ^ County Profile

- ^ Some Cities Will Be Safer in a Recession

- ^ Scott McCaffrey (2009-11-05). "Arlington Unemployment Up Slightly, Still Lowest Statewide". Sun Gazette. Sun Gazette. pp. 4. http://www.sungazette.net/articles/2009/11/05/arlington/news/nw377.txt.

- ^ "If you have questions about Arlington, we have answers". Arlington, Virginia: Arlington Sun Gazette. 23 September 2010. pp. 25.

- ^ O'Donohue, Julia (April 7–13, 2010). "Housing Market Looking Up". Arlington Connection (Melbourne, Florida: http://files.connectionnewspapers.com): pp. 2. http://files.connectionnewspapers.com/PDF/current/Arlington.pdf.

- ^ Merle, Renae (15 April 2010). "Federal aid forestalls fraction of foreclosures". Washington, DC: Washington Post. pp. A16. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/04/14/AR2010041404336.html.

- ^ Arlington County, Maryland Comprehensive Annual Financial Report, for the Year ended June 30, 2009

- ^ Facts & Figures: Zip Codes

- ^ County website

- ^ "2009 Business Travel Awards from Conde Nast Traveler" Retrieved 2009-10-27.

- ^ a b Downey, Kirstin (2007-09-07). "Arlinton County: Board Gives Go-Ahead to Eco-Friendly Taxicabs". The Washington Post. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/09/19/AR2007091902438.html. Retrieved 2010-07-10.

- ^ "All-Hybrid Taxi Fleet Debuts in Sunny Phoenix". GreenBiz. 2009-10-20. http://www.greenbiz.com/news/2009/10/20/all-hybrid-taxi-fleet-debuts-sunny-phoenix. Retrieved 2010-07-10.

- ^ Arlington Country Environmental Services Official Arlington County Government Website. Retrieved on 2008-09-17

- ^ "Capital Bikeshare has launched!". Capital Bikeshare. http://www.capitalbikeshare.com/. Retrieved 2010-09-22.

- ^ School Board

- ^ "TJHSST Admissions Statistics for 2005-06" (PDF). http://www.fcps.k12.va.us/mediapub/pressrel/tjhsstadmisstats2005-06.pdf. Retrieved August 30, 2006.

- ^ "Sister City Directory". Sister Cities International. http://www.sister-cities.org/directory/index.cfm. Retrieved 3 July 2011.

- ^ A Spy's Story in a World Of Many-Sided Betrayal, The New York Times, by Tim Weiner, February 23, 1994 dated February 22, 1994, Washington

- ^ McKinley, Jr., James C.; Dao, James (November 8, 2009). "Fort Hood Gunman Gave Signals Before His Rampage". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2009/11/09/us/09reconstruct.html. Retrieved November 9, 2009.

External links[]

- Official Site of Arlington County Government

- Arlington travel guide from Wikitravel

- Arlington's Urban Villages

- Arlington County on Facebook

- Arlington Historical Society

- Soil survey and climate summary

|

Fairfax County | District of Columbia |

| |

| Fairfax County | District of Columbia | |||

Arlington County, Virginia | ||||

| City of Falls Church | City of Alexandria |

| |||||||||||

| This page uses content from the English language Wikipedia. The original content was at Arlington County, Virginia. The list of authors can be seen in the page history. As with this Familypedia wiki, the content of Wikipedia is available under the Creative Commons License. |